Prologue

Experts in various fields of study debate whether nature or nurture has the biggest impact in the development of a child. It seems obvious to most that both factors play an important role. A perfect person from history that exemplifies the nature and nurture thesis is the topic of this “Historical Trivia” post.

Background

Tycoons of the 19th and 20th Century were given the pejorative sobriquet of Robber Barons, and all were men. Those most commonly spoken and written about are John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan, Henry Ford and William Randolph Hearst. (The same holds true today, though cultural norms are starting to include women in the same category.) But in The Gilded Age and Progressive Era of the 20th century, women were viewed as being incapable of managing large business empires or handling large sums of money.

One popular cartoon published at the time was very disparaging and divisive.

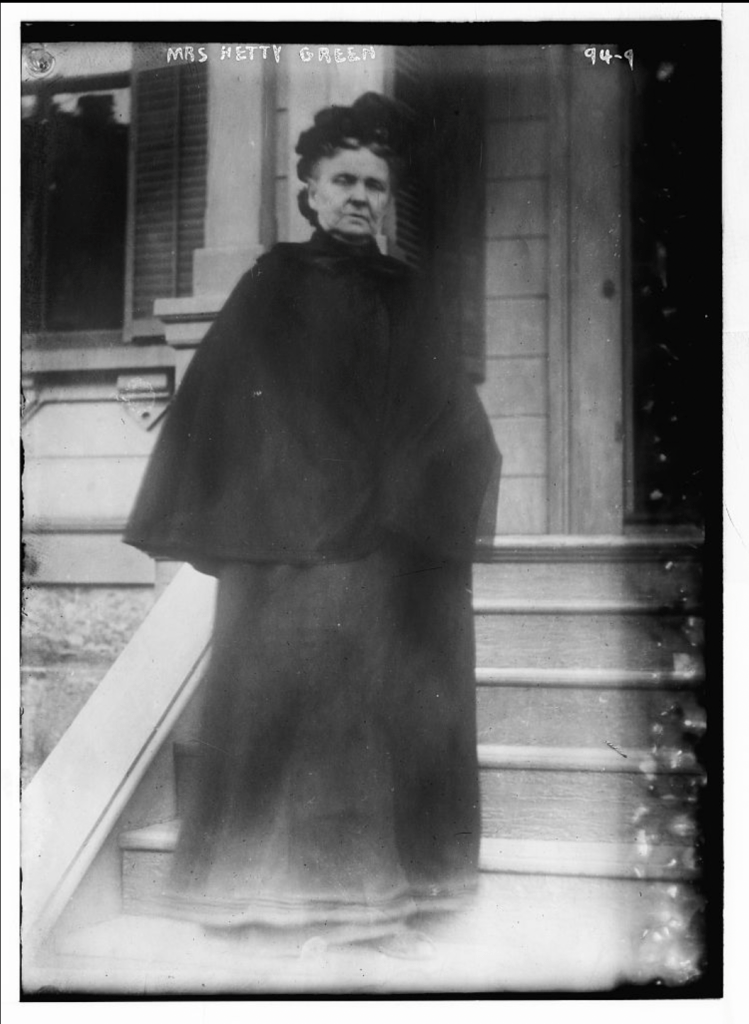

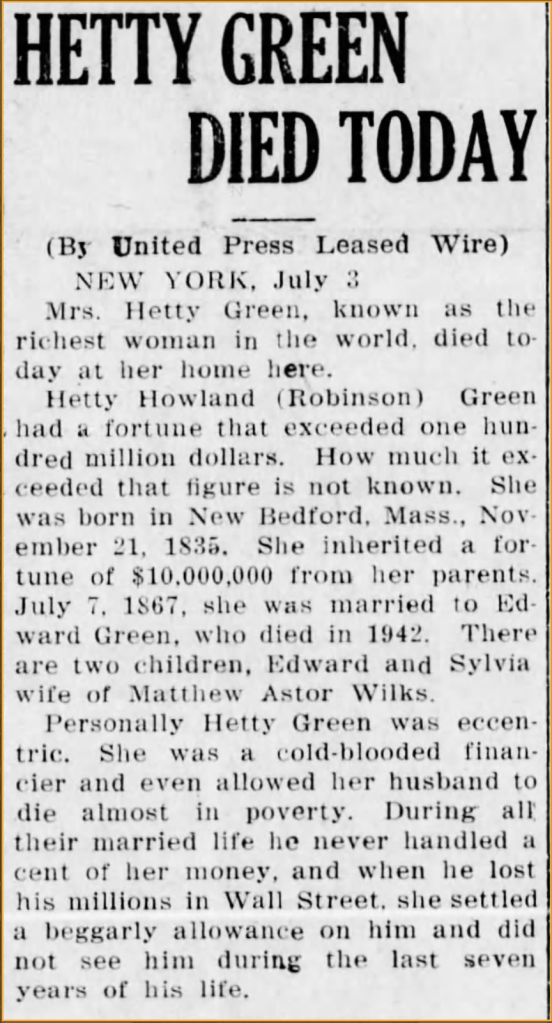

The truth is, not all Robber Barons were men. One in particular may have been ignore as a relevant wealthy business figure because she was not man; and, likely because her fortune was not gained through industrial production. She avoided that type of investing like it was a plague, and to her it was too perilous. She was commonly known by her nickname,“Hetty.” Her surname at birth was Robinson, which her marriage changed to Green. Because of her wealthy maternal ancestors, the Howlands, she also used that surname. Thus, her full name was Henrietta Howland Robinson Green, but she was and is better known as simply “Hetty” Green – and she was the wealthiest woman of that era.

Hetty’s Early Years

Commercial whaling started in America in the 17th century, specifically in New England. Between 1846 and 1852 whiling peaked, with New Bedford, Massachusetts being the hub of the industry. Born in that city on November 21, 1834, “Hetty” was the daughter of Edward Mott Robinson and Abby Howland, the richest family in the city. “Hetty” was an only child after her younger brother died in infancy, so it is not entirely unreasonable to conclude that she was being weaned to become the head of the Howland family business.

At the age of 2, “Hetty” was sent to live with her grandfather, Gideon Howland, and her Aunt Sylvia so she would have a woman’s influence – something her mother could not provide due to her mother’s continuous poor health.

Hetty’s family all were staunch Quakers, in addition to being very successful businessmen. Hetty practiced the tenets of her religious upbringing her entire life, as well as the economic and business lessons leaned from her grandfather and father.

The Howlands owned the largest whiling fleet in New England and operated a lucrative trade business of Chinese imports. Living with her grandfather, the head of the Isaac Howland Whiling Company, exposed Hetty from a very young age to the world of big business. She was so attuned to the business that she read stock quotations and commercial reports to her grandfather because of his failing eye sight. From that relationship she learned about the business as well as her grandfather’s business methods. Hetty was so attracted to business and frugal financial strategies that she opened her own bank account at age 8.

At age 10, Hetty entered boarding school in Sandwich, Massachusetts, the first of several she attended progressing through her teenage years. About the same time her grandfather died and her father became head of the company.

By the time “Hetty” was 13 she was the family bookkeeper, going with her father to “countinghouses,” storerooms, commodities traders and stockbrokers. At day’s end, “Hetty” even read the evening newspaper to her father. Her relationship remained close as long as he lived. (It was written by one journalist that Hetty was great with numbers but she was atrocious in spelling the written word.)

Adulthood

Her mother and other woman of the family were concerned that she dressed for the docks and, at age 20, had not yet found a spouse. The use of crude oil and its byproducts were becoming popular commodities, replacing the demand for whale oil and forcing Edward Robinson to leave the whaling business. The Robinsons moved to New York City and, with the assistance of “Hetty,” Edward Robinson entered a new business — stock and bond investments. His new career exposed him and Hetty to the power elite and the bon du monde of New York City.

Despite mingling with high society of New York City and her regular attendance at “lavish balls,” Hetty’s interest was less romantic and more eavesdropping with men as they exchanged Wall Street matters. The typical “womanly arts of home economics” were not her interest — business was what she wanted. She wrote of herself later, “By the time I was 15, I knew more about these things [business] than many a man that makes a living out of them.”

Hetty’s business acumen paid off when at age 30 she inherited $6 million dollars following the death of her father. Unfortunately for Hetty, woman were thought to be incapable of managing large sums of money in 1865. Of her father’s inheritance, she was given direct control over only $1 million of the $6 million. The other $5 million was placed in a trust in her name. For the remainder of her life she received the interest from the trust funds, but never had say in how the trust funds were invested.

Almost immediately after her father died Hetty became richer. Her Aunt Sylvia died within two weeks of her father’s death and she expected to inherit her aunt’s estate of $2 millions dollars. (It is claimed that Hetty believed she knew Aunt Sylvia’s will because she helped write it, unaware that her aunt had written a new will.) Someone other than Hetty had influenced Aunt Sylvia to distribute half of her money to orphans and widows and to the city of New Bedford for a new water system. The remaining half was left to Hetty, but in a trust so future generations would inherit the remaining $1 million. (Could that have been Aunt Sylvia’s way of encouraging Hetty to marry?)

Hetty contested the will which initiated a long legal battle. According to the San Francisco Call, “. . . she never refuses to see members of the press and is always ready to talk about her lawsuits, several of which she always had on hand.”

Hetty’s Reputation

The San Francisco Call, on March 26, 1899, also reported, “Hatty Green’s latest freak is to have a body guard.” That “. . . for some time past she has been living in fear of abduction, murder, robbery, arson and taxes. And the greatest fear of all is taxes, for it is to avoid paying these that she exposes herself to dangers of moving from place to place.” The paper further claimed, “. . . this strange woman has never paid a cent of taxes into the national treasury.”

In the same article about Hetty Green, the paper said that Hetty was “living in a cheap boarding house in Hoboken [New Jersey], paying for her accommodation about $5 a week. She has just moved from Brooklyn, and it is said, does not like the change.” The reporter did mention that Hetty “. . . admits, however, that she is a resident of Bellows Falls, VT, where she has a pretty summer place.”

When they, Hetty and the reporter, moved to the polar during the interview, the reporter couldn’t help but note that Hetty “lowered the gas in the house.” Obviously, to point out her intuitive nature to save a dollar whenever possible.

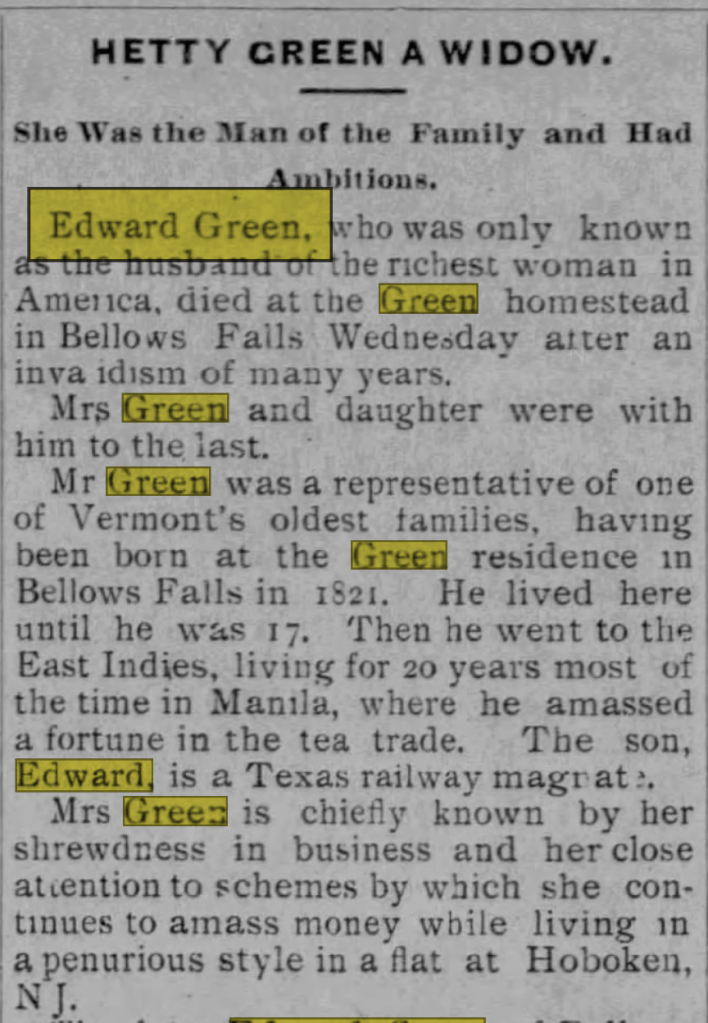

Quakers were stereotyped as “frugal” people in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Rumors about Hetty’s stinginess and extreme frugality were prolific. Misogyny may have been the root cause for many of the rumors especially when she became estranged from her husband after he went bankrupt. One rumor was that Hetty put Edward on an allowance. (Edward did have a reputation of being an extravagant spender, so it would be no surprise if Hetty decided to rain in his spending once she started paying his expenses.) Whether that rumor was true or not, it was prophetic that Hetty required a prenuptial agreement when she married Edward Green. It also proved the validity of the tenet her grandfather and father taught her: “Do not rely on someone else for money.”

Her manner of dress didn’t help dispel the rumors. She purposely (and admittedly) wore old, even shabby clothes to hide her wealth. One allegation was she wore the same under garments until they fell apart. Also, her attorney claimed she visited his office daily under the guise of friendly conversation and gossip, but really her intent was to get free legal advice.

Hetty’s Marriage

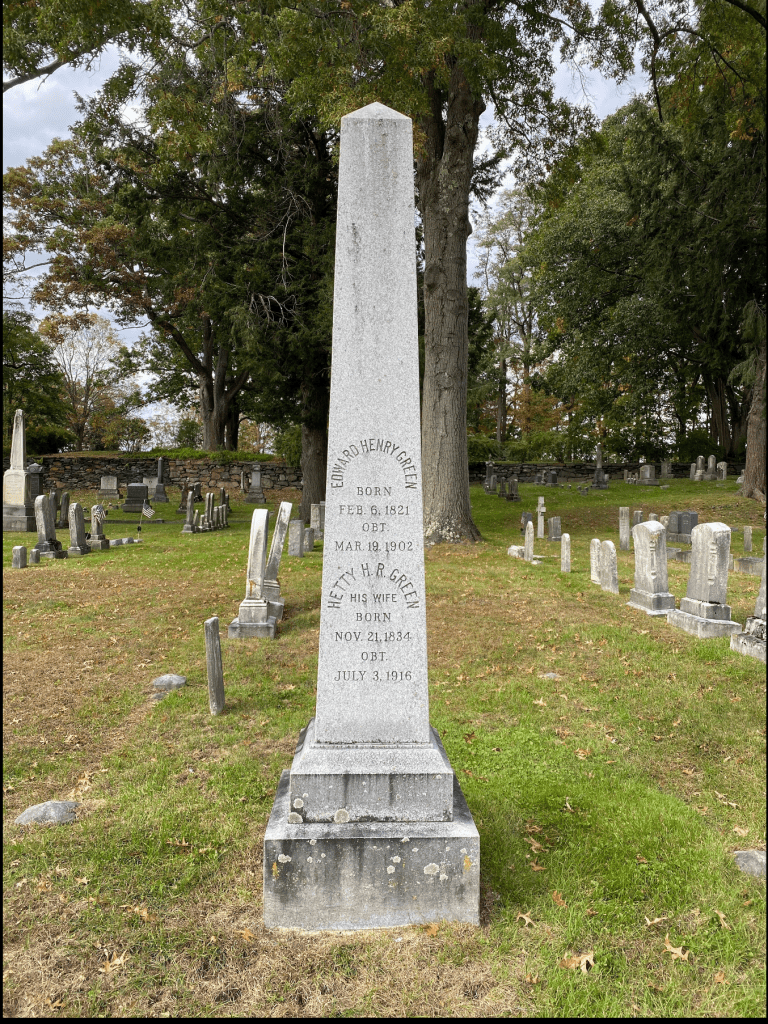

Marriage for Hetty was a dilemma. It was difficult to find a husband who wanted to marry her for love — not her money. And, she wanted a man that had business knowledge equal to her. At age 33, she seemed to have found that man in millionaire Edward Henry Green of Bellows Falls, Vermont. After the marriage she did live in Bellows Falls and London as well for a few years. The life in London was intended to shed her disappointment following the legal battle over her Aunt’s will.

Like everything Hetty did she married on her terms. The principle of providing for her own financial security taught by her grandfather and father resulted in Hetty requiring her husband to sign a prenuptial agreement, which was very unusual for the time. The agreement clearly stated that he would forgo all his rights to her wealth. Edward Green did signed the agreement, married her and together they had two children, Edward and Harriet (Sylvia) Green. Both children lived to adulthood.

Sidebar: Before Sylvia Green married Mathew Astor Wilks, her mother insisted she have Wilks sign a prenuptial agreement relinquishing his rights to her estate. Wilks, in his own right, was estimated to be worth $2 million at the time, and he signed the agreement. When Sylvia’s brother, Edward, died in 1936, his estate did not go to his widow but rather to Sylvia. Edward was a graduate of Fordham [College] University and was sent by his mother to manage the Texas Midland Railroad which she purchased through foreclosure. Edward was very successful; he turned the failing company into “. . . a model railroad boasting the first electrically-lighted coaches in the United States.” That was only one of many successful business he managed. He was also active in politics; though a Republican, he was named “A Colonel on the staff of a Democratic Governor of Texas.”

Hetty’s Reputation

It was purported that “Hetty” told her laundress she would only pay for washing the bottom couple inches of her dresses since only that portion got dirty. Even worst was the rumor she did not use hot water in order to save money. Once it was claimed she spent hours looking for a misplaced 2¢ stamp.

Another sensational rumor was that her son, Edward, lost his leg because she did not want to pay the cost of needed medical care when he was a child. Edward later denied that rumor; his leg needed to be amputated when he reached adulthood and had nothing to do with his mother’s refusal to pay for his medical care when he was a child.

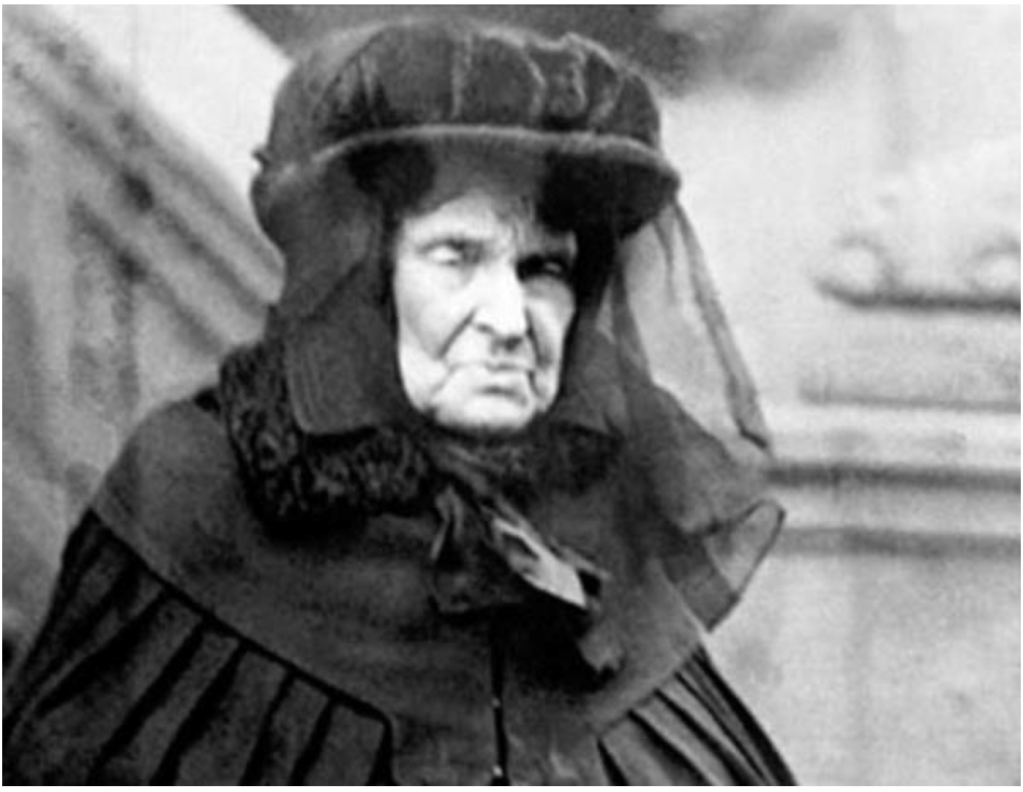

After her estranged husband died, Hetty continually wore black dresses and a black veil. Because of her business strategies and, at times, uncompromising business methods, her black attire caused others to call her The Witch of Wall Street.

Based on newspaper reports, the death of Edward Green could not be written without mentioning his notoriety was due to being the husband of “the richest woman in America.” From this death notice it seems that one of his home State of Vermont newspapers tried to acknowledge his accomplishments.

Fourteen years later, Hetty died. Her obituary was not necessarily complimentary.

Epilogue

Hetty’s will stated she wanted to be buried in the same plot as her husband, Edward Green. That decision, of course, was talked about as being another act of frugality.

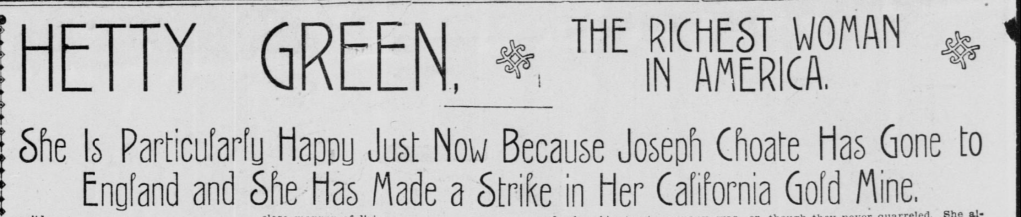

Success does often cause jealousy in others. The fact is that Hetty invested primarily in bonds, railroads and real estate; she kept away from speculating in the stock market — especially industrial stocks. Hetty despised high risk investment. She much preferred investing in things like Fishermen’s Wharf in San Francisco. Another of her holdings was headlined in The San Francisco Call – a California gold mine.

Sidebar: The reference to “Joseph Choate” is because he was usually the attorney representing Hetty’s opposition in the many lawsuits she filed. Choate also was the Ambassador to the United Kingdom under both President William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt from March 6, 1899 to May 23, 1905, and that is why he traveled to England in March of 1899.

When others were selling, Hetty had cash and was buying, then selling when the value increased. Hetty is quoted as saying:

“There is no great secret to fortune making. All you have to do is buy cheap and sell dear, act with thrift and shrewdness and then be persistent.”

Hetty felt that for a woman “safe and low was better than risky and high.” When asked for advice Hetty said:

“I regard real estate investments as the safest means of using idle money . . . Let a woman watch and see in which direction a city is going to develop and buy there.”

Henrietta Howland Robinson Green was a woman that inherited wealth, but on her own she grew a few million dollars into $100 millions at the time of her death – the equivalent of roughly $3 billion today. Her grandfather and father would be proud of her because she did it using her own business acumen, wits and Quaker upbringing.

Hetty’s investment strategies and principles, such as buying low and maintaining cash reserves, were studied and admired by many. Hetty was 81 when she died on July 3, 1916. The best way to end this summary of Hetty Green’s life is to cite from the smithsonianmag.com article The Peculiar Story of the Witch of Wall Street:

Through all of this, Green kept investing, primarily in government bonds and real estate. “Hetty died in 1916. With an estimated $100 million in liquid assets, and much more in land and investments that her name didn’t necessarily appear on,” writes Investopedia. “She had taken a $6 million inheritance and invested it into a fortune worth upwards of $2 billion [in today’s money], making her by far the richest woman in the world.” A big difference between her and others such as Carnegie and Rockefeller is that she wasn’t an industrialist. Her sole business was investing in real estate, stocks and bonds. That might go some way to explain why she didn’t leave a legacy of her name as her male peers did.

However, Green did make a material contribution to the field of investing, which shaped the twentieth century. She was an innovator in the field of value investing, which has made billionaires out of people such as Warren Buffett. Green was eccentric, but in her own special way, she was also a genius.

Do you think Hetty was “The Queen of Wall Street” or “The Witch of Wall Street?”

.