T.M. Kinney was a tailor in Springfield, Missouri for nearly 30 years. At 10 p.m. on the evening of December 20, 1905, he entered the yard of his home at 753 St. Louis street. Inside, his wife, two sons, and daughter were anticipating his arrival. Kinney rarely deviated from his habits.

Instead of the familiar sound of his key in the lock, a sharp crack pierced the night followed by a thud. The family ran to the door and found Kinney crumpled on the walk. He had been shot once and the bullet pierced his heart. He was dead by the time the family reached him.

Officers Brown and Trantham were dispatched to the Kinney home to investigate. Their investigation turned up very little. There were footprints in the snow but they were partially obliterated within minutes by more snowfall. The officers saw the tracks led north in the alley but they couldn’t trace them far. One thing, at least, became clear. There were two assailants involved.

Mr. Kinney was said to have had no enemies. The only thing the officers could learn that could lead to resentment was that the tailor once made uniforms for the railroad workers. When some did not pay him, their wages were garnished to pay their debts. But would someone murder a man for that?

Truth be told, the murder looked like a hit. Kinney hadn’t been robbed. His watch and wallet were found on the body. Indeed, if robbery was the intent, a gun wouldn’t have been necessary. Kinney was a small man and his left arm was useless to him, having never developed properly. The police believed the shooter was also small, given the angle of the gunshot.

Kinney had two older sons that no longer lived with the family. The eldest, Emmett, theorized that the murderers were lying in wait for his father to come home. The day after the murder, he swore out a warrant against W.E. Crews, a machinist who lived nearby.

“It is said that [Kinney’s] family relations were not pleasant,” the Springfield Leader hinted darkly. “It is known that he and his son, Emmett, were not on friendly terms with each other.”

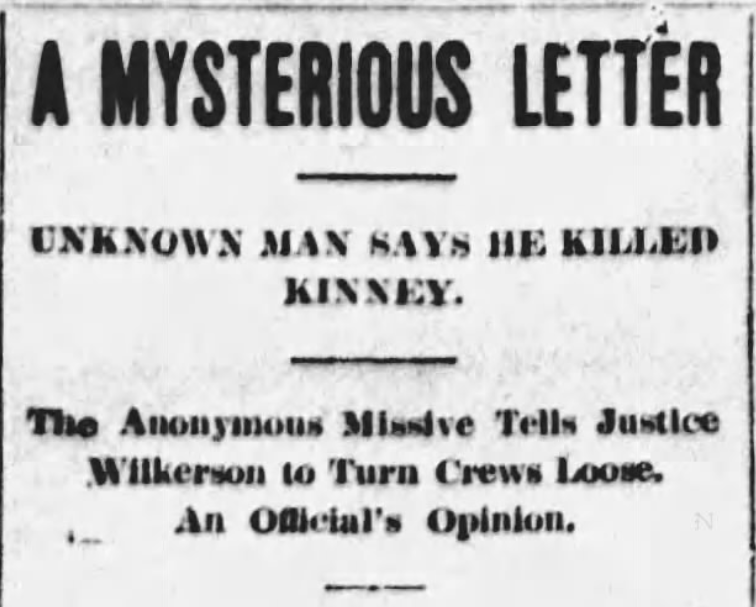

At the inquest, the jury cast doubt on the charge against Crews. He had a strong alibi and swore he had no hard feelings against the tailor. On December 23, Justice Wilkerson decided there was no reason to detain Crews and released him. The following day, an anonymous letter arrived at the judge’s chambers.

“Justice Wilkerson: Old man, turn Crews loose. I’m the guilty guy, and by the time you get this I’ll be in Mexico. I killed Kinney, Amen.”

Instead of a signature, the writer drew a picture of a man’s right hand.

The Springfield Leader sniffed at the communication. “The letter was written on a poor grade of stationary, one sheet of ordinary tablet paper being used,” they reported scornfully. “It was written with a lead pencil and the penmanship was bad, as was also the punctuation and paragraphing. It had evidently been written by a man employed in some shop or factory, since the letter and envelope were covered with finger prints, made by hands that had the ordinary black grease from machinery on them.”

The police had no way of checking the fingerprints. One detective told the paper he didn’t believe the writer was in Mexico. It was a hoax to throw the law off the killers’ trail.

Ten days after the murder, Willard Caldwell and Elmer Hancock, both age 20, were arrested. Police acted on a tip from a relative or close friend of one of the boys. Initially, only their names and ages were released.

On January 12, a short article ran about the arrest:

After a preliminary investigation, Hancock was released and Caldwell was kept in custody.

Emmett Kinney again intervened. He worked with the District Attorney to swear out a warrant for Hancock, who was again taken into custody.

Despite the two suspects being in jail, the reward for the capture of the tailor’s murderers grew from $200 to $500. It seemed as if people didn’t believe Caldwell and Hancock were really responsible.

Hancock was eventually released again. There was no evidence against him. Willard Caldwell remained in custody. He had a criminal record but still there was little evidence he was involved in this crime.

Caldwell was tried in August for the murder, but he got a hung jury, with 10 voting to acquit and 2 to convict. He was set to be retried in December but as the date approached, the prosecutor met with the judge. He didn’t think he could get a conviction, he admitted. The judge nodded. It wasn’t a strong case. So Caldwell was released after a year in jail.

No one else was arrested or tried for the murder of T.M. Kinney. This case has a number of parallels to Frank Richardson’s murder in Has It Come to This? Both men were murdered with a gun by a small person at Christmastime in Missouri, five years apart. Both victims were said to have had unhappy home lives and two suspects were named in both cases.

To return to this case, it seemed Caldwell couldn’t stay out of trouble. He was indicted again in November 1907 for being part of a gang of three men who committed a violent assault against two younger boys. Caldwell admitted to cutting the boys but swore he acted in self defense. I didn’t trace his case further but it didn’t look great. Elmer Hancock successfully disappeared from the headlines, and hopefully went on to have a happy life.

Now that you’ve heard the facts, what do you make of this case?