New York has always been a tough city, even for its elite residents.

Let’s examine the case of Mayor William J. Gaynor, the 94th mayor of the Big Apple.

The mayor was known to be a philosophical man, often quoting the Greek stoic Epictetus. The perfect man, Epictetus said, would not display anger toward a wrongdoer. Gaynor often reflected on this theme and adopted the old Greek’s belief that philosophy was the practice of virtue and insensibility to pain was a mark of it.

The son of an Irish blacksmith, Gaynor was a judge before becoming the mayor and he was strongly associated with Tammany Hall machine politics.

Gaynor promised well: he had that unique flare so many New York mayors are wont to exhibit. For instance, on January 1, 1910, he walked from his home in Brooklyn to City Hall for his inauguration, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge in his top hat. As one does. He spoke without much fanfare, and promised to do his best for the city.

The mayor was popular but Tammany Hall soon became disenchanted with Gaynor. He simply would not go along with the program. His most serious violation seems to have been hiring based on a record of success instead of the time-honored tradition of payoffs and “recommendations” for highly-paid civil servant roles. Repeated demands and bullying had no discernable impact on the new mayor, and local politicians who felt entitled to these roles for themselves and their friends were aggrieved.

Eight months into his term, disaster struck. The mayor was going on vacation. He was aboard the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, which was bound for Europe, and briefly docked at Hoboken, New Jersey. Mayor Gaynor stood on the deck, greeting well-wishers and the press.

As this was taking place, a nondescript man by the name of James Gallagher came aboard the ship. He had recently been dismissed from the city’s Dock department and his repeated messages to the mayor demanding his reinstatement had failed. He had come for vengeance.

Gallagher nonchalantly asked a priest which of the men was the mayor. The priest obligingly pointed Gaynor out. Gallagher made his way into the circle until he was within point-blank range. Then he shot the mayor in the head, hitting his jawbone and throat.

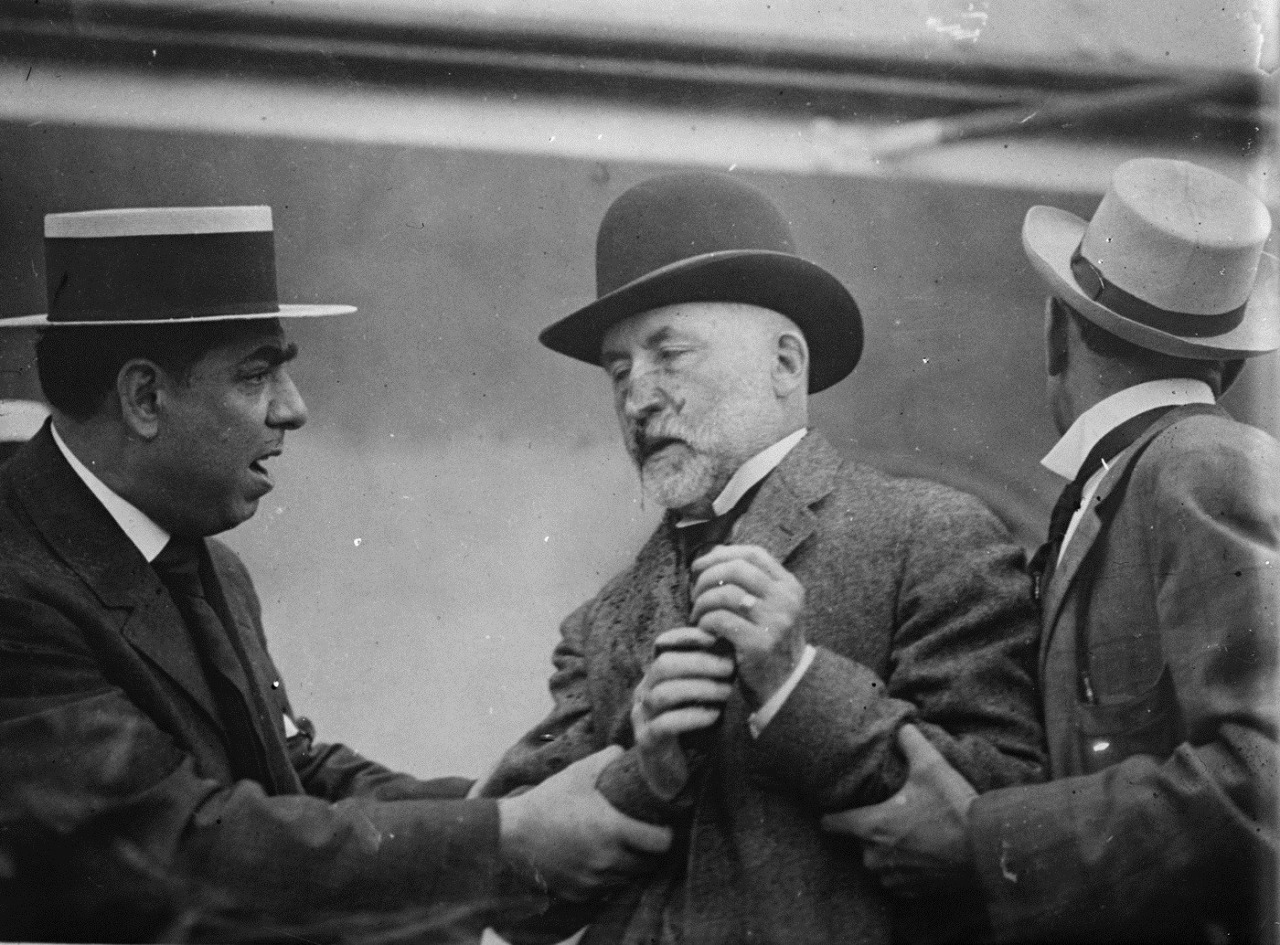

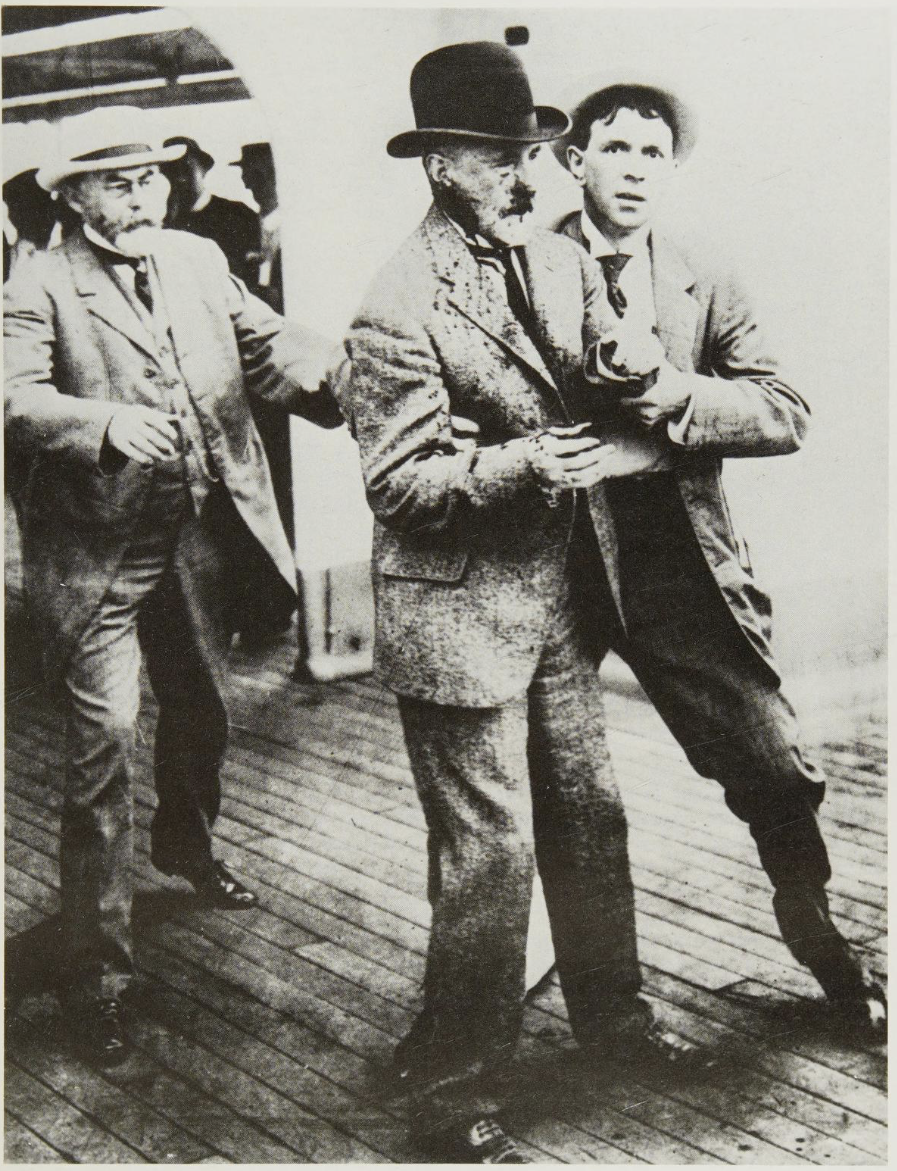

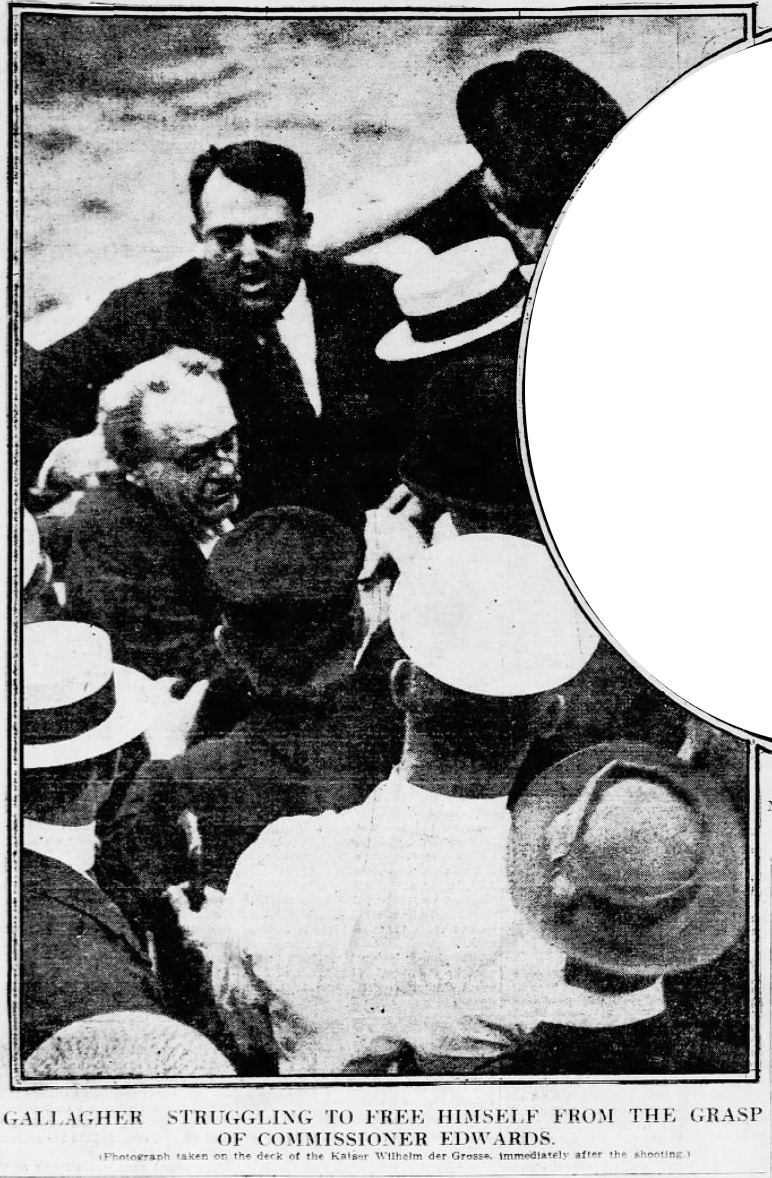

William Warnecke, a New York Tribune photographer, was there to photograph the mayor’s departure and instead took this famed shot, just after the attempted assassination as two men came to Gaynor’s aid.

Street Cleaning Commissioner “Big Bill” Edwards was present. He leaped on Gallagher as he fired a second time. Big Bill took the bullet in his own arm, probably saving Gaynor’s life.

Edwards is uppermost in this photograph, holding on to Gallagher to prevent a further attack. Edwards refused to let go until the Hoboken police took the would-be assassin prisoner.

Gaynor was evidently a sincere and honorable man. He lived by the precepts he espoused publicly. His only comment before losing consciousness was simply, “This is a pity.” He was quickly spirited away to nearby St. Mary’s hospital. Meanwhile, the “crank” Gallagher was led away in police custody.

News of the attack on Gaynor spread quickly, and concern and well-wishes poured into New York City. Over 1600 miles away, the Texas Sheriffs Association was gathering for the first day of their annual convention when word reached them of the attack on the mayor. Putting aside their agenda, they denounced the attack on Gaynor and expressed their deep sympathy for the mayor and for New York City. Rather than a minister opening the convention with a prayer, all the sheriffs stood and recited the Lord’s Prayer in a show of solidarity for Gaynor.

Gaynor recovered surprisingly quickly but he carried the bullet in his throat for the rest of his life. He was wildly popular in New York. Gaynor’s profession being politics, he quickly learned to use his injury to his advantage. When confronted with unpleasant topics, Gaynor would wave away the subject saying, “Can’t talk! The fish hook in my throat is bothering me today.”

Despite his popularity, Tammany Hall would have none of him. The Democratic nomination went elsewhere for the next election, but Gaynor was nominated anyway by an independent group and his chances for a second term were good.

Evidently, the mayor was not a superstitious man. In September of 1913, he once again set sail for a vacation in Europe, traveling aboard the RMS Baltic. And this time, he would not come back. He was relaxing in a deck chair when a sudden heart attack ended his life.

I don’t know much about his politics, but I can’t help admiring the independence and toughness of a uniquely American character like William Gaynor. He’s someone New York can be proud of!