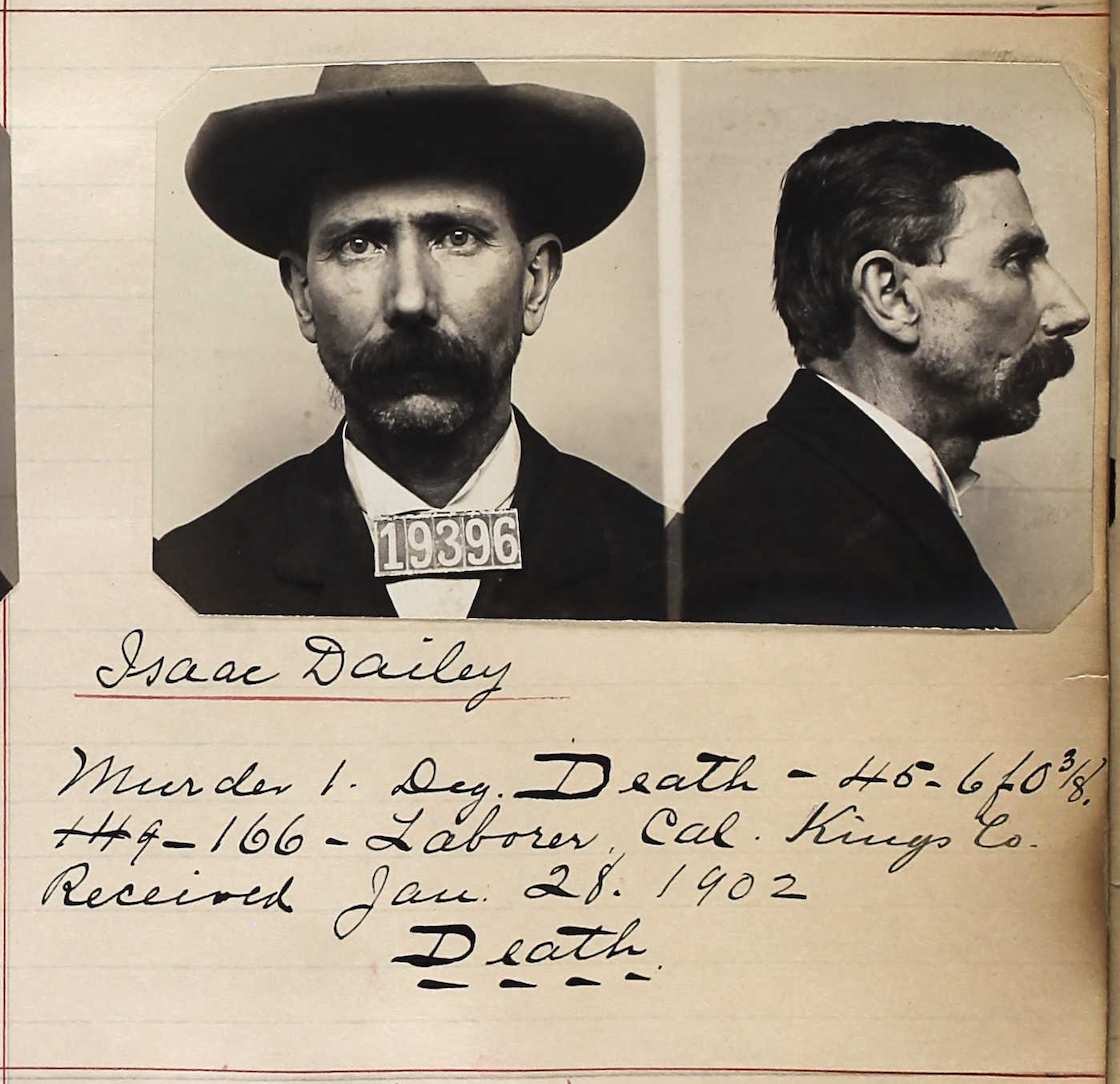

This is Part 2 of my 3-part discussion with Taylor Northcutt, from Prosopa Insights, about physiognomy and mugshots. I was truly impressed by Taylor’s analysis of Isaac Dailey’s mugshot, and I think you will be too!

In 1900, Isaac Dailey, known as Ike to friends and family, was a laborer in Hanford, California which is situated about 30 miles south of Fresno. Ike was a troubled man who drank a lot and was subject to “fits,” possibly related to the syphilis he had contracted nearly 20 years earlier.

His crime was as simple yet inexplicable. Ike took his bicycle to Lemuel Metz, a jeweler and general repairman, to fix the front wheel. Metz fixed it but Dailey damaged it again soon after. He returned it to Metz, who did not charge him for the second repair. On July 10, Dailey damaged his bike a third time. When he brought it to Metz, the repairman said he would charge for the repair.

Ike was incensed. He seemed to believe Metz was obligated to continue fixing the wheel in perpetuity. He stormed off but soon returned, drunk and armed with a shotgun. Metz was working on another repair and unaware Ike had returned. Without ceremony, the disgruntled man shot the repairman in the back. Within a few minutes, Metz died, leaving behind a wife and six children.

Dailey was tried for the murder in September. The jury rejected his Not Guilty by reason of insanity plea and convicted him. The Hanford Morning Journal provided this description of his sentencing on October 2, 1900:

“It is the order of this court that you be taken by the sheriff of this county and delivered to the warden oi San Quentin Penitentiary and by him kept in solitary confinement until Friday, February 21st, between the hours of 11 a.m. and 2 p.m., when you be taken by the warden and hanged within the walls of the prison by the neck, until you are dead, and may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

While the sentence was being passed a death-like silence reigned. All that could be heard was the trembling voice of the judge.

Dailey was returned to his cell and when a Journal reporter saw him he was pacing his cell, smoking a cigarette. The reporter shook hands with him. He was still very nervous and cold.

He said he had no recollection of committing the crime. He was sorry he did the deed and thought the punishment was great, but that he intended to die like a man. He wants to see his father, who lives near Huron, and a sister-in-law. Sheriff Buckner has granted the request if it is possible to do so.

Dailey says he believes in a God and a future life beyond death. He believes he will go direct to heaven at the moment of death, but judging from the profane oaths that fell from his lips, we fear Dailey and God are not on very intimate terms.

Through various legal machinations, Dailey’s attorneys managed to prolong his life a full year. California Supreme Court refused to grant a new trial and, in mid-February, Governor Henry Gage refused his plea for clemency.

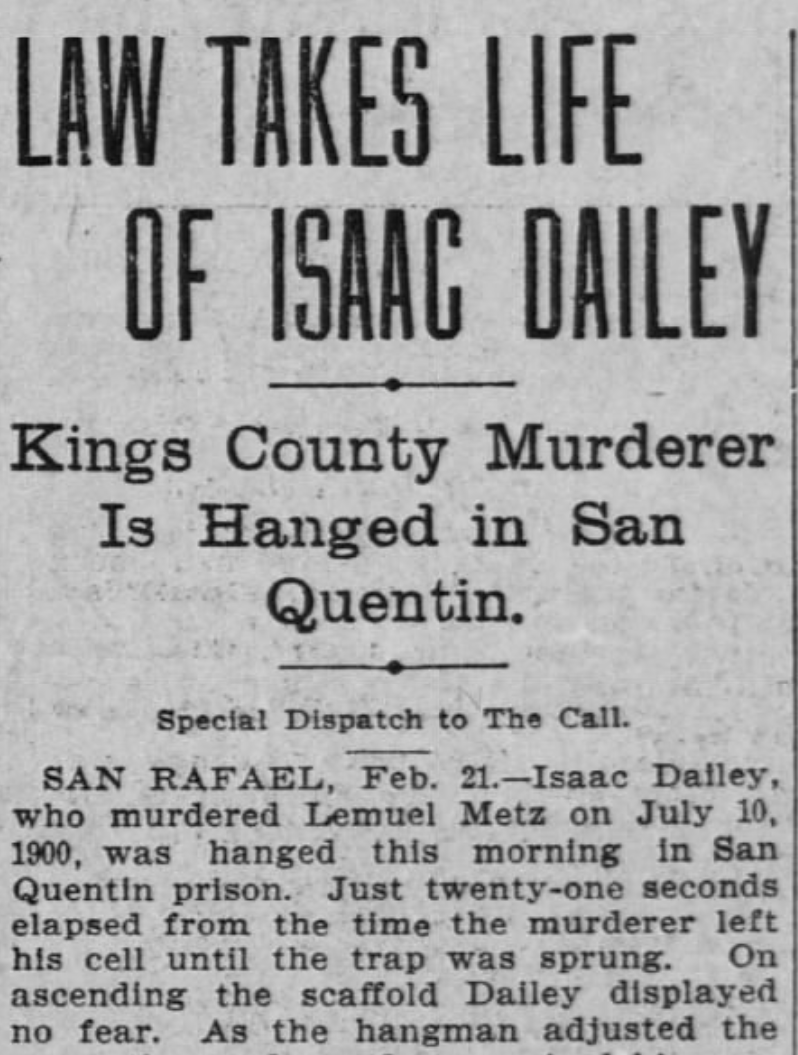

On February 21, 1902, justice came for Ike. According to the San Francisco Call:

On the morning of his death he sent for Sheriff Buckner of Kings County. When the sheriff appeared, Dailey said: “When I go to the gallows this morning I will do so without fear. I will die with a clear conscience in the fact that I know when I shot and killed Lemuel Metz I was insane or I would not have done it. That was nearly two years ago, and I have had much time to realize the enormity of my act, but nevertheless I will die with a clear conscience. I want to thank you for the kind treatment I received while incarcerated at Hanford and also, through you, I want to thank my friends for their strenuous efforts in my behalf. Now I am ready to go.”

According to the Call, “Just twenty-one seconds elapsed from the time the murderer left his cell until the trap was sprung.” This was probably a typo and it was 21 minutes. Either way, it didn’t take long. Dailey showed no fear as he ascended the scaffold. He clenched his fists when the black cap was slipped over his head. At 10:40 a.m., Warden Aguirre gave the sign and the trap fell. The resentful, brooding spirit of Isaac Dailey was no more.