This is the last part of the story of the famous con woman, Cassie Chadwick. Want to read the story from the beginning? Click here!

Cassie’s game finally came to an end after she received a loan for $190,000 in November 1904 from a Massachusetts banker. Shortly after making the loan, the banker learned of the exorbitant sums Cassie had already received from other financial institutions. He immediately called his loan in. Cassie had already spent a great deal of the money and couldn’t pay it. The banker sued her and the whole game unraveled. Carnegie was consulted and denied knowing Cassie or signing a promissory note to her or anyone else.

By the time the extent of her fraud was discovered, Cassie had even cleaned out her husband, Dr. Chadwick. Like Dr. Springsteen, Cassie’s first husband, Dr. Chadwick attempted to cover his wife’s debts, but it was obviously far more than he possessed. He filed for divorce before leaving for Europe, leaving Cassie to her fate. The checks he had written to repay friends bounced.

Cassie brazened it out a bit longer, making vague references to powerful people who would come to her aid, but the jig was up. She fled to New York City to evade arrest but the law caught up with her quickly and arrested her at her expensive hotel, as her maid and son looked on.

A crowd was gathered at the depot when her train rolled in. They called out mockingly to her as she was ushered into the jail. Two deputies walked her up three flights of stairs to the row of cells where she would stay. While Cassie examined her new digs in Cell 14, the Chadwick Mansion on Millionaire’s Row was inhabited only by the maid.

Cassie’s fraudulent activities and the enormous sums concerned even caught the attention of J.M. Lewis, the Houston Daily Post columnist who was the first poet-laureate from the state of Texas. In the December 14, 1904 edition of the paper, he composed this poem:

In 1905, Chadwick stood trial in Cleveland. Her trial was attended by Andrew Carnegie and many of her former neighbors from Millionaires’ Row.

Carnegie was there mostly out of curiosity. He was said to have given Cassie a “sweeping glance” when he entered the courtroom. I would guess Cassie felt gratified by his presence.

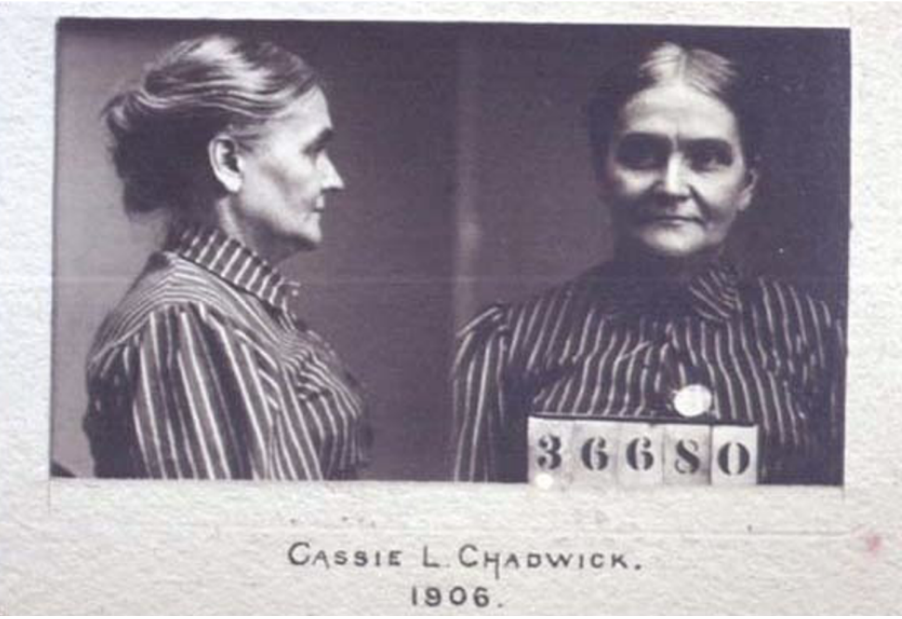

On March 10, 1905, Cassie was convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison and a $70,000 fine.

She was sent to the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus in January 1906. Prison did not agree with her. Her health went to pieces and she died there on October 10, 1907.

Cassie fascinates people—her life and criminal career are so strange that even her old home on Euclid Avenue was a tourist attraction until it was demolished 15 years later.

But why did she do it? She could have stopped while she was ahead many times. Was it something in her past that was driving her? We know little of her life before she came to Cleveland, other than the stunt at the bank. She was one of eight children who grew up on a farm in Canada. She didn’t have much education but apparently had beautiful penmanship. She wanted to write but, according to her sister Alice, Cassie just didn’t have the imagination to write fiction. She apparently stayed with Alice for two weeks when she first moved to Cleveland, and when Alice was out of town visiting family, she returned to find Cassie had sold the furniture.

As for how she did what she did, we don’t really know that either. The two prevailing opinions are that Cassie had a unique hypnotic power over men and/or people loved the idea of being close to a really powerful person like Andrew Carnegie. But what do you think: Do you buy these explanations of Cassie’s criminal career? Or was there something else happening here?