Musical accompaniment: Cocaine by Hoyt Axton.

This is Eugene Dalton. His photo was taken by Lewis Wickes Hine in 1913, when Dalton was 16 years old and he worked as a messenger boy in Fort Worth, Texas.

The photographer penned this succinct summary of Dalton’s case:

“For nine years this sixteen year old boy has been newsboy and messenger for drug stores and telegraph companies. He was recently brought before the Judge of the Juvenile Court for incorrigibility at home. Is now out on parole, and was working again for drug company when he got a job carrying grips in the Union Depot. He is on the job from 6:00 A.M. to 11:00 P.M. (seventeen hours a day) for seven days in the week. His mother and the judge think he uses cocaine, and yet they let him put in these long hours every day.

He told me ‘There ain’t a house in ‘The Acre’ (Red Light) that I ain’t been in. At the drug store, all my deliveries were down there.’ Says he makes from $15.00 to $18.00 a week.”

Lewis Wickes Hine was clearly appalled by the boy’s situation and it does sound shocking. Today, it seems inexcusable for a teenage boy to be in a situation like that.

But sometimes the context makes a big difference–and people are a little too apt to be outraged, especially about the past. In Eugene’s case, when I looked at each part of his story individually, it didn’t seem that bad to me.

I’m not sure what was meant by the charge of incorrigible. The definition is “incapable of being reformed.” (I imagine many of us fall into that category!) But in what way was he incorrigible? Was he violent or committing crimes? That would make a difference. But it seems like most of Eugene’s waking hours were spent at work. I wonder what made him incorrigible?

The work he was doing was not great. Then again, at the time, most kids in his socioeconomic class worked full-time by age 16. The average weekly wage for full-time manual labor in the south was $9-12 a week, so he was doing better than most people. If you adjust for inflation, he was making $485 – $580 a week, which is very good for a 16-year-old. And no doubt most of the money was used to support the family.

The cocaine use too, isn’t quite what it seems today. In 1913, anyone could buy cocaine over the counter in the United States. Cocaine, opium, and other narcotics were advertised as pills, liquid, or as ingredients in cough syrup and products marketed toward children and infants. The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act passed in 1914, requiring narcotics only be dispensed by doctors.

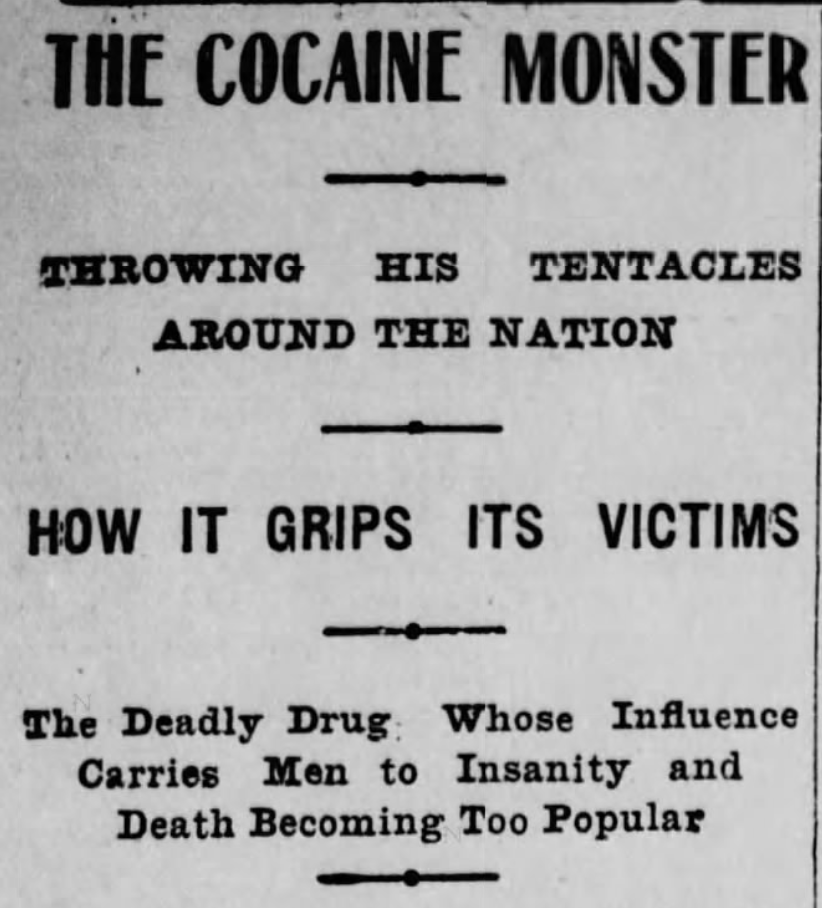

On that last point, cocaine was suspected of being a dangerous stimulant long before the narcotics law passed. I’m not surprised that Mrs. Dalton and the judge were concerned about the boy’s drug use. As early as 1898, articles condemning the drug were appearing in newspapers across the country.

Of course, this isn’t a defense of 16-year-olds taking cocaine and running errands in the red light district for eleven hours a day. But some of these shocking stories are much more understandable when you put them in context.