This is the conclusion of the Legend of Lorraine Gordon. Click here to go to Part 1!

In January of 1929, Lorraine was in Portland charged with a different crime. “Mannish attire for girls on nights when goblins galivant in glee may be all right, but when a pretty 19-year-old girl persists in masquerading as a boy its time to call a halt,” the Morning Register advised. The official charge against Lorraine was masquerading. She was guilty, the judge acknowledged, but he let her go with a warning that “trousers are for boys and not petite, brown-haired girls.”

At the beginning of August, Lorraine was brought to Santa Clara County Hospital with a broken vertebrae from a car crash. But by August 13, she was back in Oakland and ready to lean in to her Girl Bandit career.

One thing that makes her case confusing is that her last name kept changing. At this phase of her story, the papers referred to her as Mrs. Cassida, Mrs. Booth Cassida, and Lorraine Gordon Booth. I’m guessing she remarried and Mr. Booth, whoever he was, was quickly discarded.

On August 13, Lorraine and a friend of hers named Allen Herbert (alias Al Reed) robbed the Elmhurst branch of the Bank of Italy. The Oakland Post gave a fantastic account of the robbery and its aftermath.

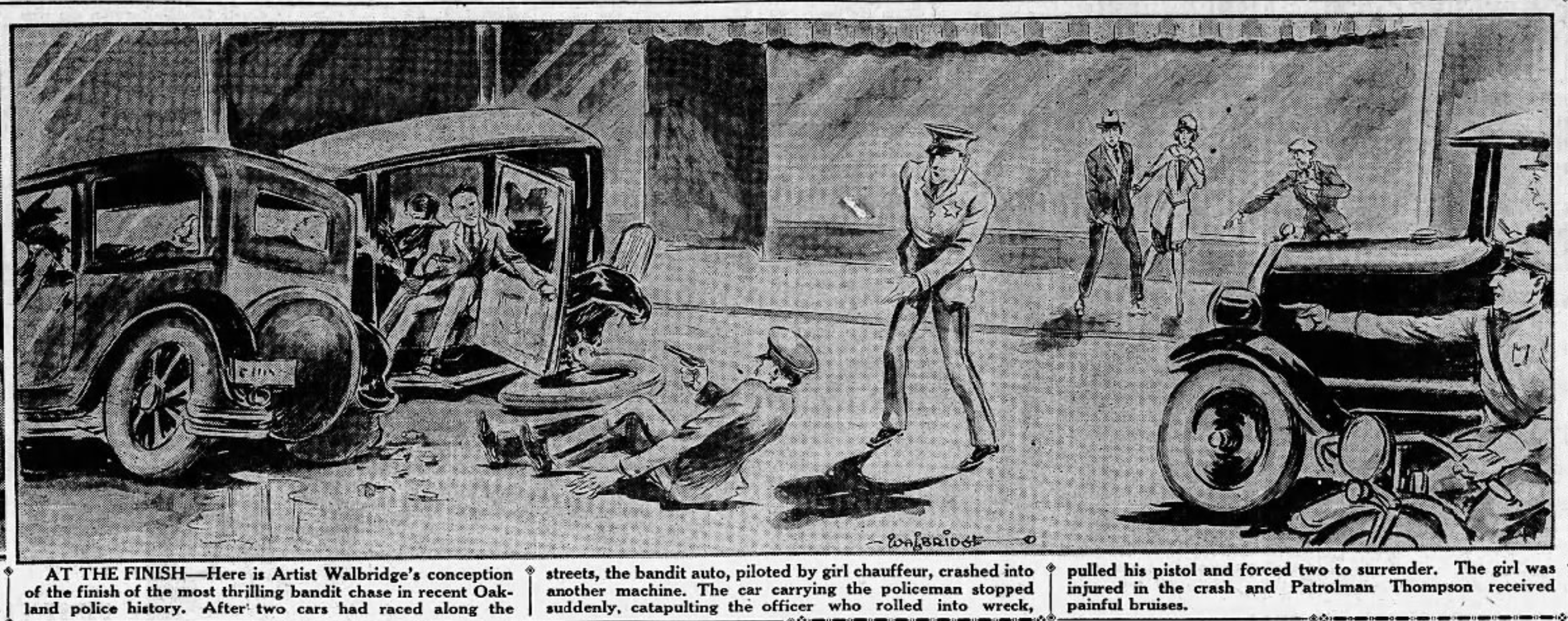

“Herbert entered the bank alone for the holdup yesterday afternoon. His girl partner remained at the wheel of the running car. Shoving a note that read “Give me all your money” to Davidson, Herbert brandished a gun. Davidson gave him $500 and the bandit fled. R. B. Schuler, 483 Forty-third street, saw Herbert brandish the gun and gave chase in his automobile. He picked up Policeman James Thompson, who clung to the running board of the car as it careened in pursuit of the fleeing bandit machine. Motorcycle Officer Leo Brandt also gave chase when the speeding bandit car flashed by him.

When the bandit car crashed into [Omaha tourist] Alwine’s machine, Schuler stopped his car so suddenly that Thompson was hurtled into the wreck. He landed on his feet with his gun in hand. Patrolman D. C. Luster, on duty at the corner, also rushed to the scene.”

The couple had actually made off with $665, which was found tossed in the back of the getaway car. Unfortunately, Lorraine had reinjured her broken vertebrae in the crash, and she was taken to a hospital.

When he was arrested, Herbert told police that he was a war veteran and married to a prominent socialite in New York. They had two children. Herbert admitted the robbery but insisted that Lorraine was an innocent bystander. “She’s a good kid. She didn’t know I was going to hold up a bank. I’m to blame. I forced her to drive on when the cops chased us.”

By now, the Oakland police were familiar with Lorraine. They dismissed Herbert’s attempt to shield her and determined a uniformed officer needed to guard her hospital room to prevent another escape.

While she was at the hospital, a reporter came to see her. What made her steal? The reporter asked. What made her find friends amongst crooks and gangsters?

Lorraine smiled. “Guess I’ll have enough talking to do later. Guess it won’t help to talk about it. Besides I don’t want to….my mother reads the papers,” she said. “What’s the use? I’m caught and I’ll have to take what I get.”

Lorraine and Herbert were charged with conspiracy to rob the bank and the robbery but I didn’t find any charges related to the getaway car chase. Their case was heard by Superior Judge Homer Spence in September. Both pleaded not guilty but they didn’t have much of a case. Herbert’s gallantry in trying to absolve Lorraine of all guilt was squandered when the defense counsel stipulated the girl had written the hold-up note.

The jury delivered a guilty verdict, and Willard Shea, the public defender, immediately suggested that “Mrs. Cassida be sent to the Ventura reform school.”

The judge shook his head. “She already has escaped two or more times from the Ventura school. To send her there again would do no good.”

Lorraine and Allen were sentenced to five years to life in San Quentin prison.

Allen Herbert was visibly depressed after the sentence was handed down, but his accomplice seemed as carefree as ever.

“Lorraine, are you downhearted about the verdict?” someone called to her.

“Hell no!” she answered cheerfully.

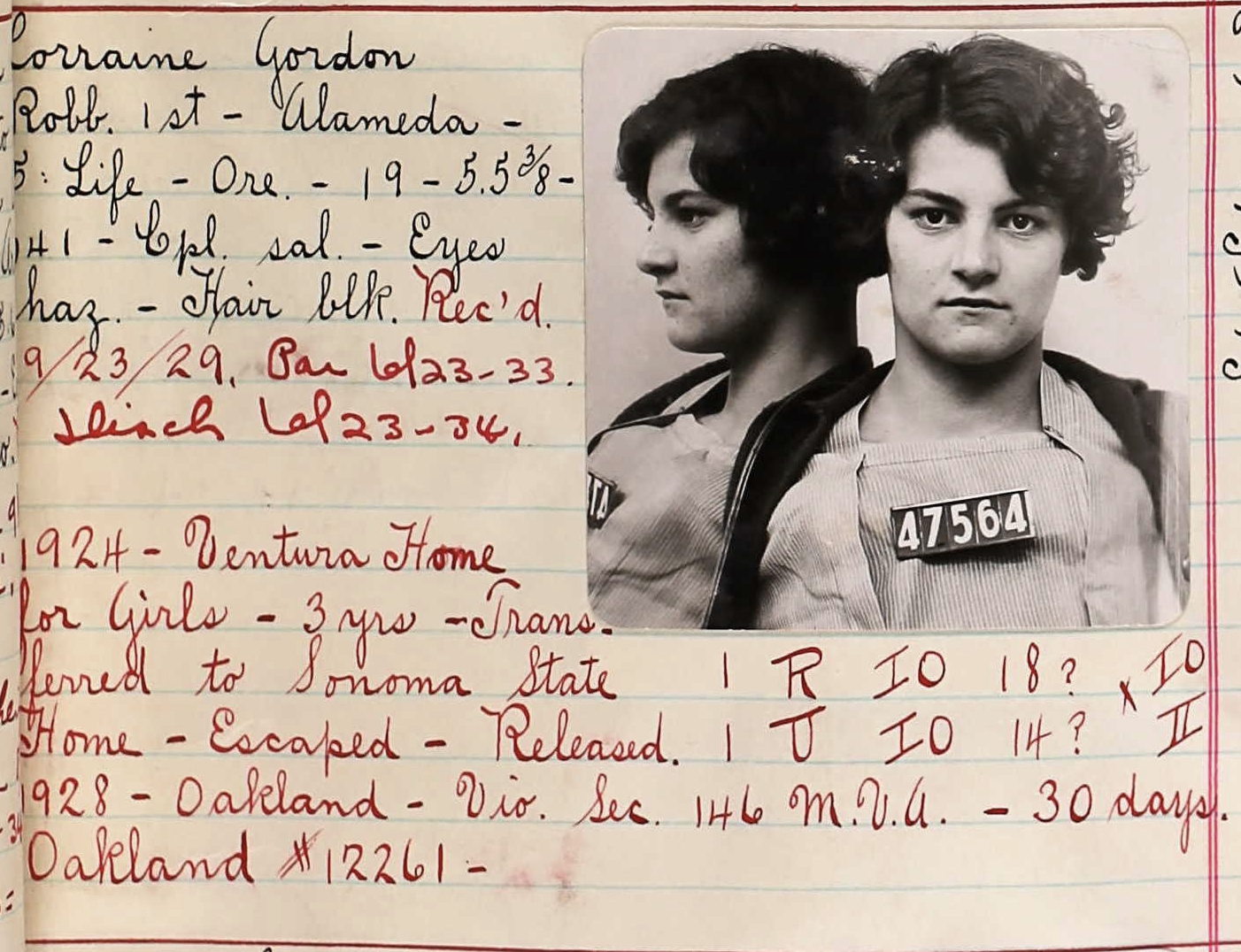

Lorraine was received into San Quentin on September 23, 1929, and paroled on June 23, 1933. She didn’t reoffend while she was on probation—or at least she wasn’t caught!—so her probation ended on June 23, 1934.

This post is absurdly long already but sometime I want to do a little digging and find out what life after San Quentin was like for Lorraine.

Perhaps she went to business school.