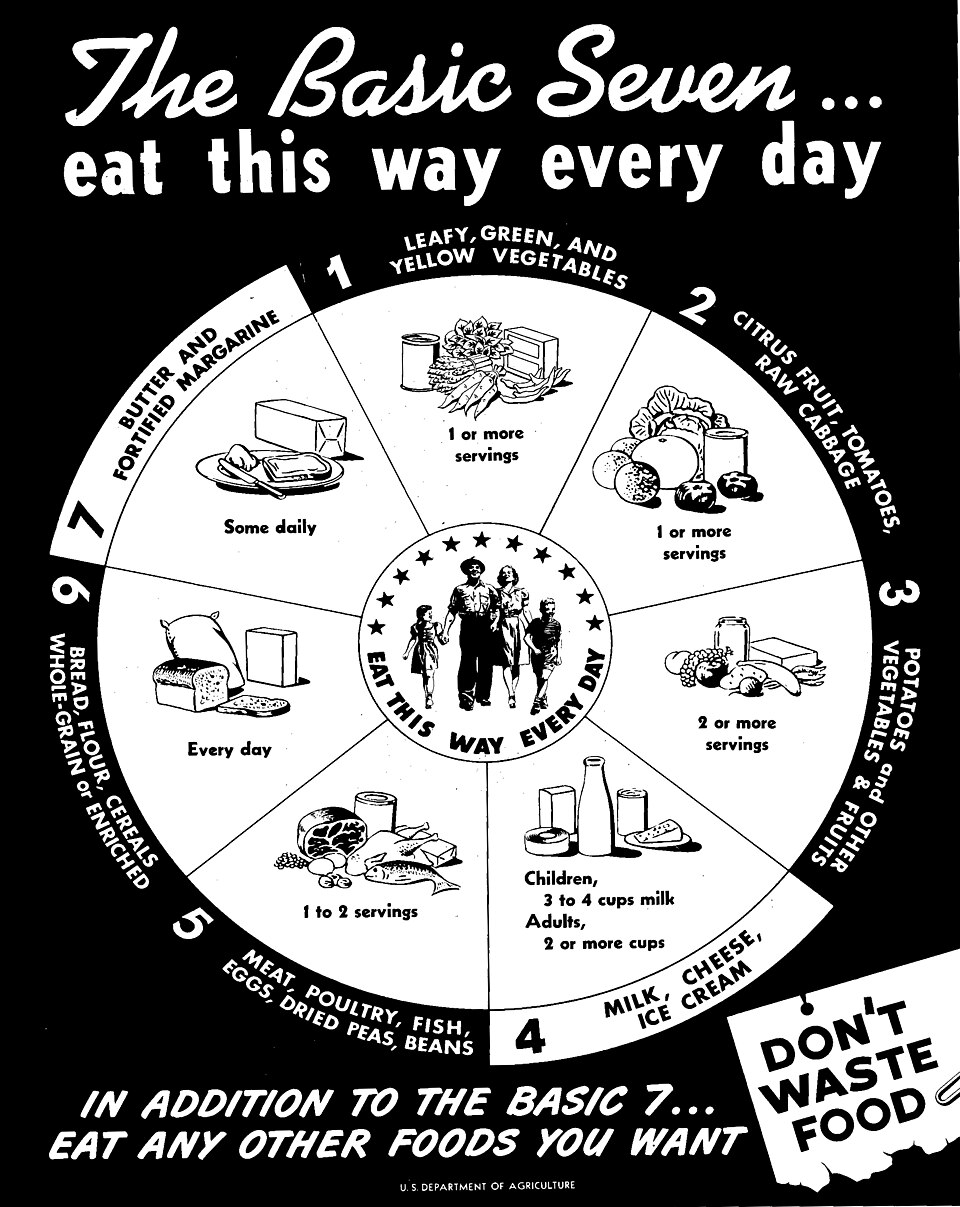

Yesterday, I uncovered a belief I’ve had ever since I was a child. It was so ingrained in me that I didn’t consciously realize it was there. It was something a teacher had said which was, at best, a matter of opinion. But it remained lodged in my mind all this time and negatively shaped the way I thought about that topic. A better example may be the food pyramid, or its precursor the Basic Seven, which was taught to generations of children as fact, yet modern nutritionists have disavowed it.

It’s a strange and freeing feeling to remove a false belief. Our beliefs about the world, humanity, situations, and ourselves define what is possible. If I believe all blue-eyed people are diabolical or that any man with a mustache is trustworthy, it impacts how I interact with the world–not to mention throwing me into a state of helpless confusion whenever I encounter a blue-eyed man with a mustache. It doesn’t matter if it isn’t true. If I convince myself of it, I’ll act as if it’s true. It’s worth excavating our beliefs and dragging them into the light to reckon with them. Where did the belief come from and how would the world be different if you no longer accepted it?

Repetition is one of the most powerful forces in the world. People are far more likely to uncritically accept and act on repeated words and thoughts. You can put this to good use for yourself with mantras or affirmations. “I am confident and friendly.”

It can also be used for bad. Repetitive chanting is a feature at any gathering related to cults and ideological movements. In his 1895 book The Crowd, French psychologist Gustav Le Bon explained how the repetition of short phrases has a numbing effect on the mind and prevents people in groups from thinking clearly. In that benumbed state, they become suggestible and very easy to manipulate.

If you’ve never read E.M. Forster’s wonderful book Howards End, I highly recommend it. Forster understood human nature very well. At the beginning of the story, Helen Schlegel has a brief infatuation with a young man named Paul Wilcox. It fizzles, much to her sister Margaret’s relief. As luck would have it, the Wilcox family rents a flat opposite the Schlegels’ home. Margaret is worried about how Helen will react, particularly if their cousin Frieda eggs her on.

Oh yes, it was a nuisance, there was no doubt of it. Helen was proof against a passing encounter, but—Margaret began to lose confidence. Might it reawake the dying nerve if the family were living close against her eyes? And Frieda Mosebach was stopping with them for another fortnight, and Frieda was sharp, abominably sharp, and quite capable of remarking, “You love one of the young gentlemen opposite, yes?” The remark would be untrue, but of the kind which, if stated often enough, may become true; just as the remark, “England and Germany are bound to fight,” renders war a little more likely each time that it is made, and is therefore made the more readily by the gutter press of either nation. Have the private emotions also their gutter press? Margaret thought so, and feared that good Aunt Juley and Frieda were typical specimens of it. They might, by continual chatter, lead Helen into a repetition of the desires of June.

Beliefs are unconsciously formed and we’re subjected to repeated messages. One thing that is within our control is detailed visualization with action. The experts, including the great Neville, tell us to dream fantastical waking dreams and continuously take small steps toward that dream. I call it planting seeds. Often you don’t see any value in doing so–the step seems too insignificant. It’s the sum of these little actions and being vigilant about seizing opportunities that makes this technique work. Sometimes one stray seed can grow into a tremendous plant!

What a thread I’ve been raveling! Over and out!