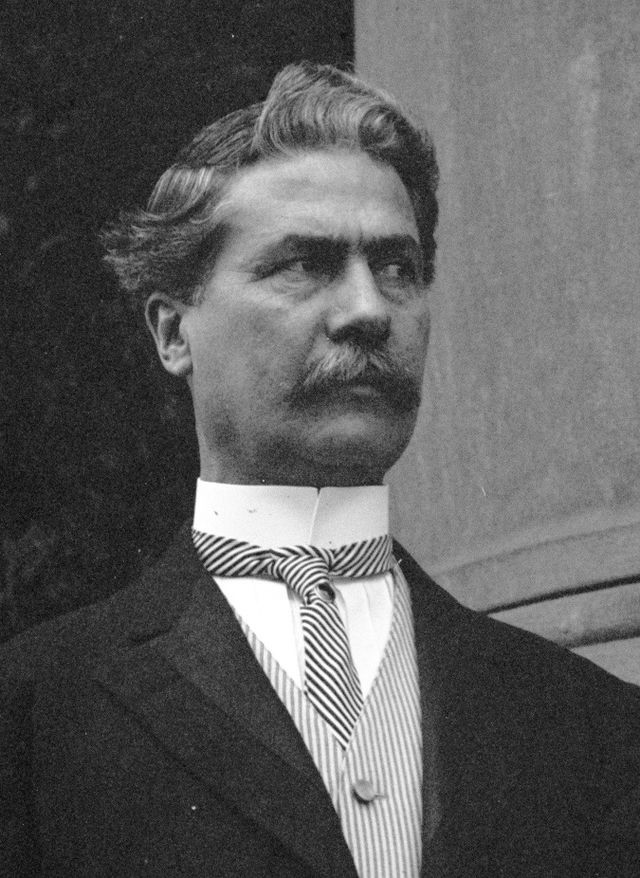

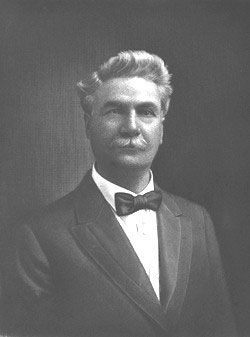

Meet Coleman “Cole” Blease, the mustachioed governor of the great state of South Carolina from 1910 – 1915.

Governor Cole Blease is an intriguing man. There’s no doubt he was a flawed man, but nobody is all bad or all good. I present him to you, as he presented himself to the citizens of the day.

When Governor Blease assumed office, South Carolina was in the throes of civil unrest. Many farmers were giving up the land and going to work in the mills, in quest of a living wage. Black and white, men and women, children and adults were thrown together for the first time – with the only commonality being an unfamiliar environment. The results were frequently chaotic and violent.

This little girl was photographed by Lewis Hine, working in a Newberry, SC mill:

Cole Blease didn’t create the stormy environment in South Carolina, but he contributed to it. The governor worsened tensions between black and white workers with racist tirades. Black men, he told audiences, would gain the right to vote just as surely as poor white men would lose it.

It’s also safe to assume the governor was no suffrage advocate. He was violently opposed to women “doing society” instead of staying home with their families. He warned the men working in mills that the aim of women was to “give us their dresses for our pants.” (No word on how the governor figured out our secret plan.)

Blease was an advocate of lynching, which seems especially odd for someone whose profession was ensuring law-and-order. “An aroused mob is an outraged community which carries out the law, but brushed aside the law’s technicalities and delays,” he proclaimed. When mobs brushed aside technicalities like criminal trials and juries, Cole Blease publicly rejoiced with what the papers called a “ritualized, bizarre dance”.

Cole Blease sounds like a regular beam of sunshine, doesn’t he? But there was more to him.

For instance, the governor generously funded the schools in South Carolina, stressing the importance of longer school terms, high teacher salaries, and better school libraries. However, he strongly opposed requiring children to attend and publicly decried child labor laws.

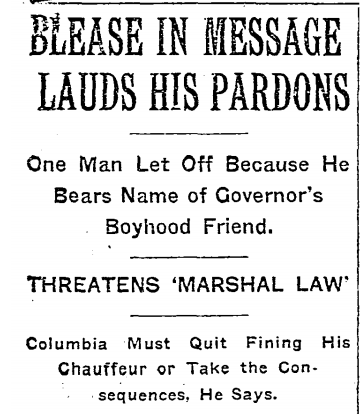

Blease thoroughly enjoyed paroling and pardoning convicted criminals, including Charley Hall, who was, of course, a black man. For someone with a dubious reputation on racial matters, Blease pardoned prisoners of all races with equal rapidity.

It’s difficult to tell what would make for a persuasive parole application to the governor. The prisoner’s guilt or innocence was irrelevant.

In one case, the governor pardoned a prisoner named Lester Bryant. After communicating with the prison, Blease’s deputy informed the governor that Bryant had escaped while working on a chain gang in Greenville County.

“Pardon him, anyway,” Blease ordered. Authorities were unable to locate Bryant to let him know he didn’t have to go back to jail.

William White was convicted of murder in 1912 and paroled by Blease just a few months later. “It was an unfortunate occurrence,” the governor conceded, “but he bears the name of one of my best boyhood friends during my boyhood days.” The governor was well aware that the murderer was a different person.

Estimates vary but Blease paroled at least 2,000 convicts while he was governor, whose offenses ranged from murder to bigamy to larceny of bicycles. There was a public outcry but Blease refused to listen saying, “The people of the nation would be horrified if they knew of the fearful brutality practiced in our prisons, the merciless whippings, the electric shocks, the other forms of shocking cruelty.”

Were you wondering what Cole Blease thought of carbonated soft drinks? If so, you’re in luck because it so happens he made a statement: “I now call your attention to the evil of the habitual drinking of Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, and such like mixtures, as I fully believe they are injurious. It would be better for our people if they had nice, respectable places where they could go and buy a good, pure glass of cold beer, than to drink such concoctions.”

The governor resigned five days before the end of his term, and disappeared from public life for nearly ten years.

In 1924, he reemerged to win the Democratic primary and went on to serve a term in the U.S. Senate.