The State Archives of North Carolina has a fascinating book called Era of Progress and Promise, 1863-1910 by W.N. Hartshorn. The book was published in 1910 and it profiles how Christianity and education shaped the lives of black Americans post-emancipation.

I’ve only read about ten pages of the book and flipped through the first quarter of the book but I plan to return to it. You couldn’t help but be impressed by what the people in this book managed to achieve.

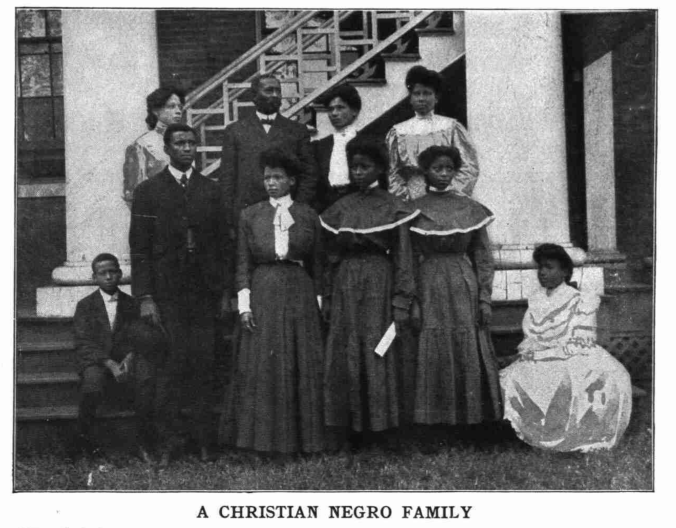

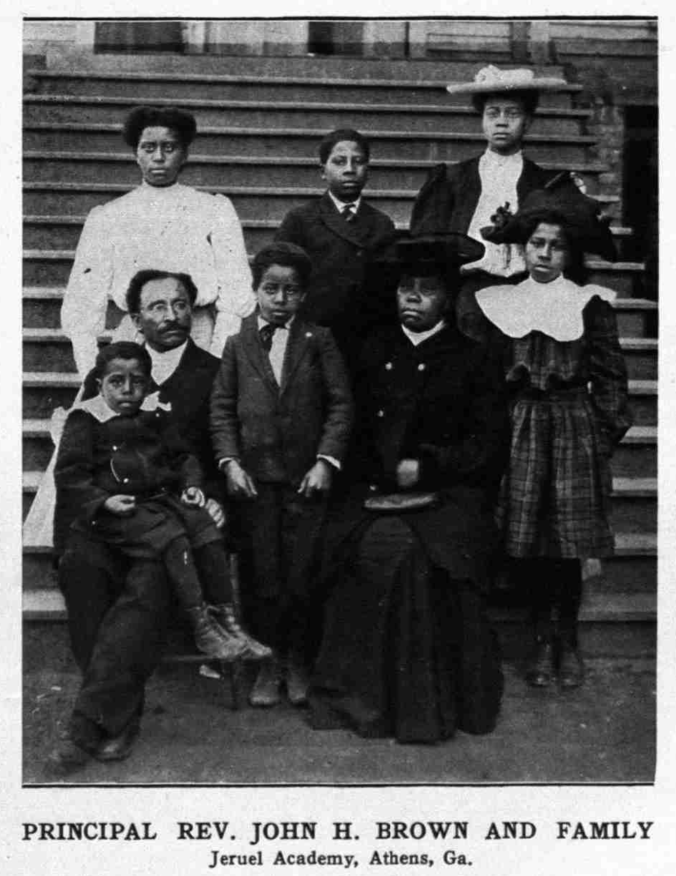

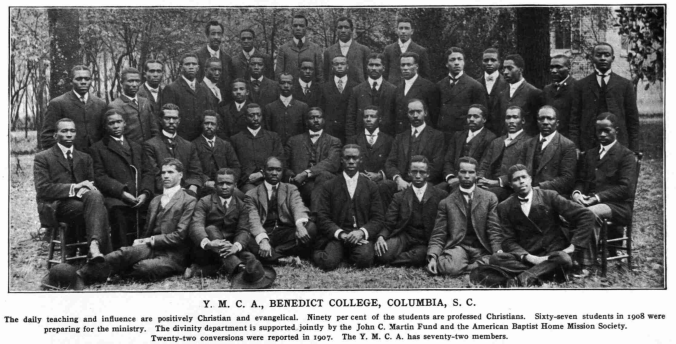

Of course, I got derailed when I started looking at the pictures in the book. I love seeing the way people carried themselves at the turn of the century. Not just the clothing and hairstyles, but the demeanor. When I was younger, I thought Victorian era people were just serious. They probably were serious comparatively, but what I missed is that we lack something they had: quiet confidence and dignity.

Strangely enough, that confidence and dignity seem nearly universal in that age, whether you were a Russian empress, a stage actor, a midwestern farmer, or in this case, black students and educators in the south.

Before I tell you what else I noticed, I’ll share a couple of pictures of families in the book.

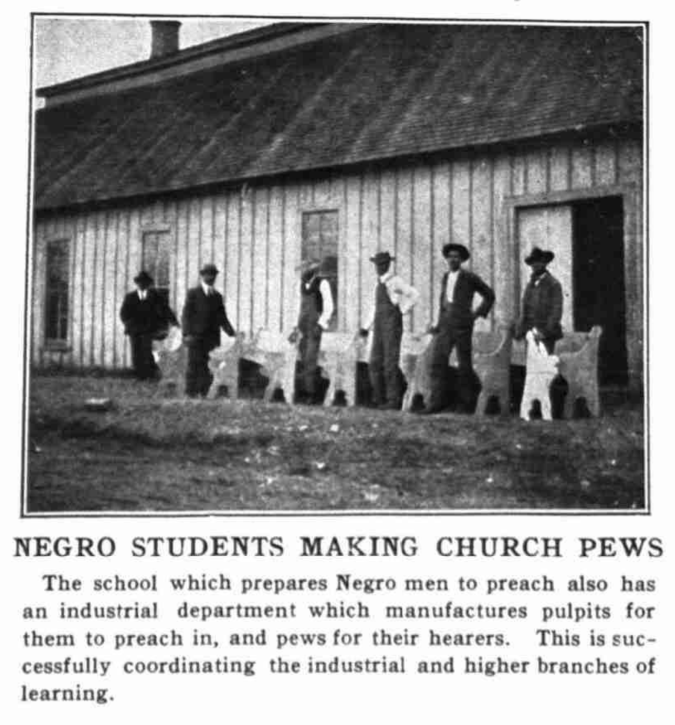

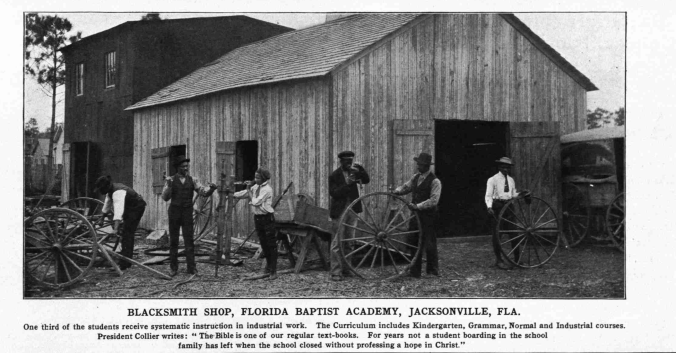

The other thing I noticed is the approach to education that these people took, which blended specialized classes with related practical training. For instance, a lot of the male students in the book were attending seminary, and planning to become preachers. So the schools also taught them how to make church pews.

On the surface, seminary students making pews seems like a quaint idea but it’s smart. For one, it’s something a preacher (in that time) might be expected to do sometimes. Also, if you couldn’t get a job as a preacher right after seminary school, your odds of eventually becoming one would dramatically increase if you had a skill like building pews that the church might hire you to do. It puts you in the place where you want to be, interacting with people you want to be with. And, even if nothing went as the student hoped, making furniture is a practical skill he could use to support himself.

For comparison, imagine a kid today who spends four years and thousands of dollars on an economics degree. After graduation, he’s got a lot of ideas and no experience or skills. Universities tend to treat practical skills as something the employer should provide, as on-the-job training. But employers don’t see it that way. Why would they hire someone with no skills or experience who wants to be paid well because he has a degree? So the kid becomes a Starbucks barista instead. Maybe he discusses Keynesian economics in the break room, but essentially he’s wasted his time and money on a university education. It seems to me that the old approach of blending theory, practical experience, and complementary skills is far better.

We’ve forgotten more than most cultures and countries ever knew. At least on this question of education, maybe the answer isn’t to dream up something new but to return to what worked.