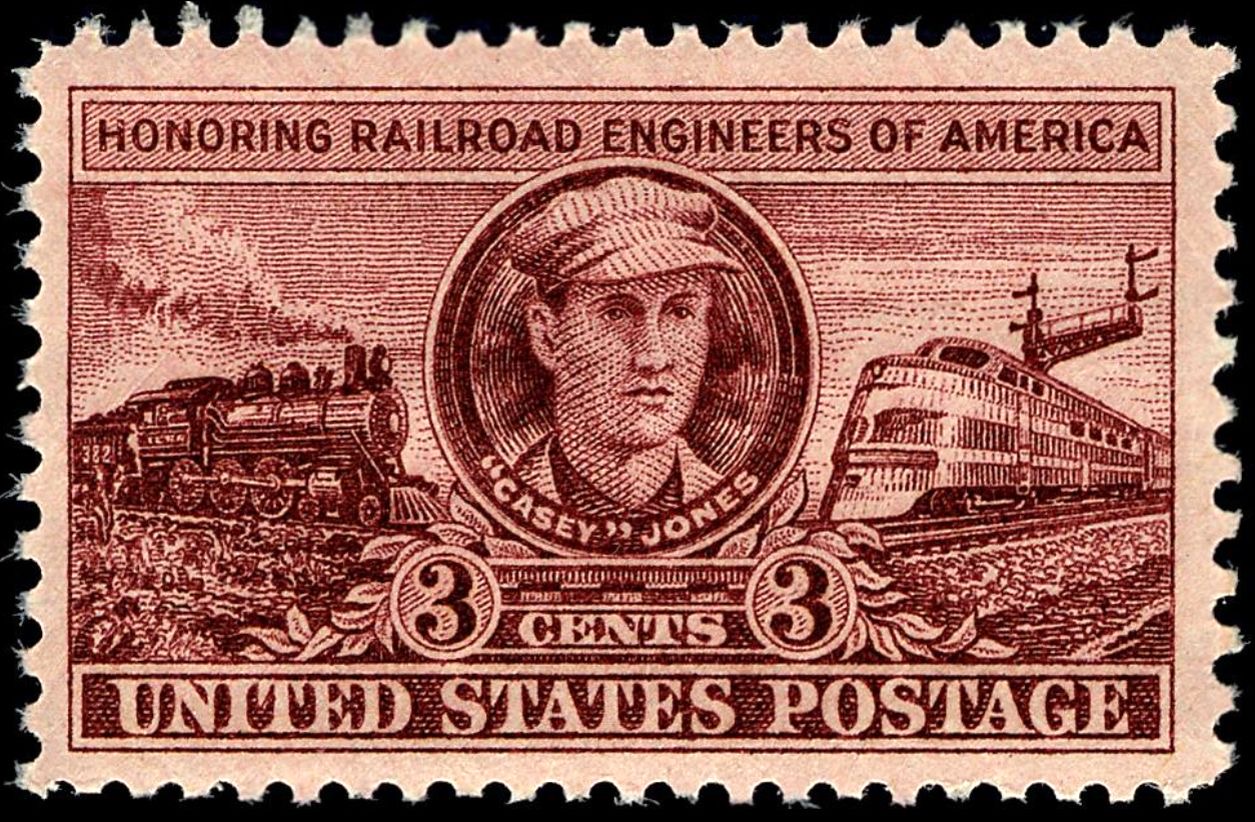

Have you heard of Casey Jones? I knew the Grateful Dead song about him long before I knew anything about the man himself. All I really knew was that he was a locomotive engineer whose train crashed.

Musical accompaniment: Casey Jones by the Grateful Dead.

Jonathon Luther Jones was born in Missouri in 1863. As a child, he lived in a small town in Kentucky called Cayce, which led to his being known as Casey. As a teenager, he began working with the railroads.

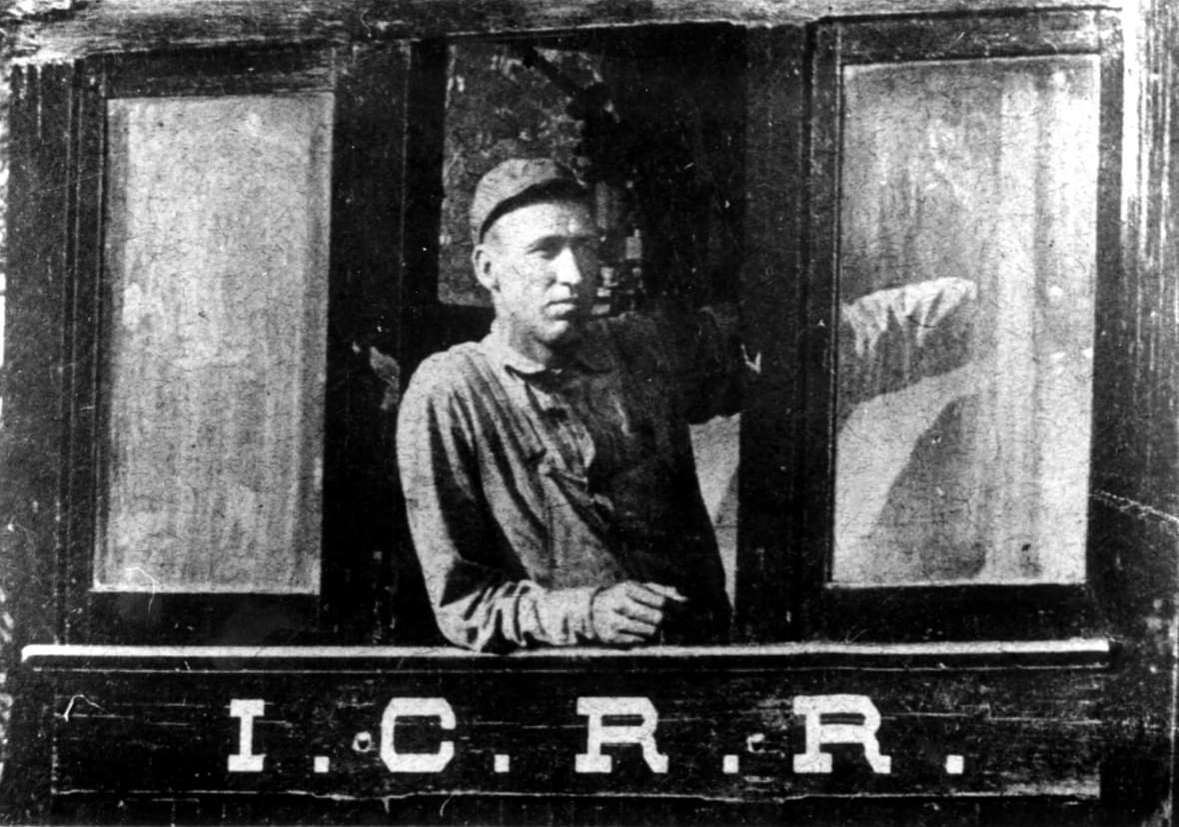

Jones married Miss Mary Brady at the age of 23, and obtained a job at Illinois Central Railroad, which was based in Memphis, Tennessee and Jackson, Mississippi. The Joneses had three children and settled in Jackson, Tennessee. Casey’s modest home, photographed by Carol Highsmith, is a museum today,

Casey was well-liked and reliable. It was a point of pride for him to be punctual. He often exceeded normal speeds to arrive at his destination on time.

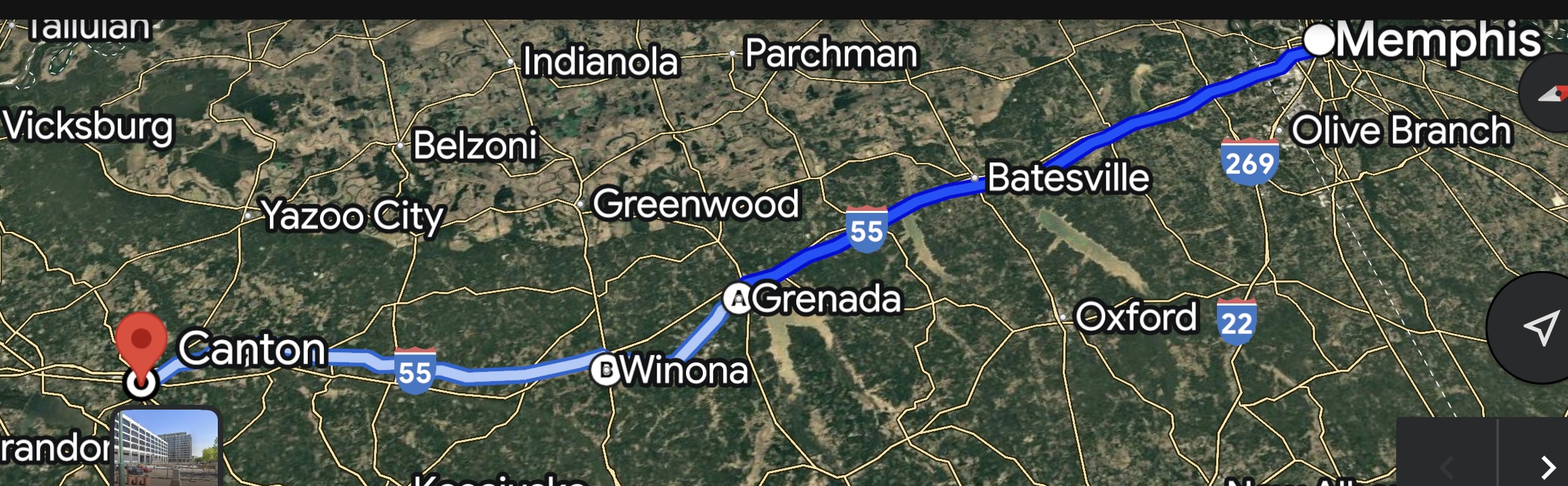

On April 29, 1900, 37-year-old Casey was due to leave Memphis at 11:35 p.m. to run the passenger service to Canton, Mississippi. The train was delayed and didn’t Memphis until 12:50 a.m. Despite this 75-minute delay, Casey was cheerful and confident he could make the time up. That night, he was driving the ten-wheeler No. 382, a powerful engine called the Cannonball. He was accompanied by fireman Sim Webb.

The weather was foggy in the early hours of April 30, and the Canton run was known for its sharp curves. Nevertheless Casey drove rapidly, around 80 miles per hour.

By the time they reached Grenada, the train’s delay was reduced to 20 minutes. At Winona, the train was only five minutes behind. Casey exultantly told Webb they may arrive in Canton on time after all.

Disaster struck in Vaughn, Mississippi. Three trains were there but the main line was supposed to be clear for No. 382 to pass. An air hose broke as the workers were moving the last engine off the main line. The brakes locked and four railroad cars were stranded directly in Casey’s path.

No. 382 was hurtling toward Vaughn, traveling at 75 miles per hour. Jones’ eyes were on the track in from of him but Webb had a better view from where he stood. He was the first to catch sight of a stranded caboose on the track ahead of them.

“Oh, my Lord!” the fireman shouted. “There’s something on the main line!”

Casey jumped up and looked over the boiler. He sized up the situation instantly. Without a second’s delay, he shut off the steam, reversed the throttle, and hit the airbrakes hard to activate an emergency stop. A crash was inevitable; these measures were taken to reduce the severity of it. “Jump Sim!” he yelled. “Save yourself!”

Webb was poised to leap. He turned back and urged his friend to jump too.

“No!” Casey Jones shouted. “I’ll stay at my post!” They were his last words.

Webb leapt into the darkness. The last sound he heard was the high-pitched train whistle—Casey’s warning to anyone near the track. The fireman didn’t hear the crash. His fall knocked him unconscious.

the music is back!

was Casey high on cocaine?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I’m glad you like the music! Technically I’m not sure if he was high but I doubt it, lt’s provably just that “high on cocaine” rhymes with “driving that train”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on what I know, Casey didn’t consume alcohol. It unlikely he used any type of drug.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Paul Harvey, a famous broadcaster for ABC News Radio, signature line was, “Now the rest of the story.” An additional bit of history, and an anecdotal event about Casey Jones, with a better ending, is provided by the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Even before his fateful train wreck, Casey was known as a hero. In his 1939 book, Fred J. Lee describes an 1895 occurrence in which Casey, noticing a group of small children dart in front of the train, leans out on the cowcatcher and pulls a small girl from the train rails to safety.

Casey’s wife, Mary Joanna “Janie” (nee Brady) Jones, never married again. Janie lived until age 92 in Jackson, TN, in 1958. She worked diligently to protect Casey name as well as to protect the true events surrounding the accident. According to Time.com, in 1928, Janies filled a lawsuit against a studio planning to produce a movie about Casey without her permission.

The media even was “semi-snarky” when writing about Janie’s participation in the 80th Anniversary Celebration of the railroad in the area. Time.com reports, ” ‘Widow Jones,’ who the magazine [Time] had noted ‘looks well and buxom,’ later called that TIME story ‘a conglomeration of lies.’ (For example, Engine No. 638 was not in fact the number of the train on which Casey Jones died.) In her letter to the editor, she warned TIME to never again attempt to write about the Casey Jones story without her permission.”

Mrs. Casey Jones in her home in Jackson, Tennessee, 1956, Department of Conservation Photograph Collection

When Janie died, Time finally attempted to set the record straight when it printed:

That legend was a legacy of bitterness to Janie Jones, Casey’s wife, mother of his daughter and two sons. For the next 58 years she lived with The Ballad of Casey Jones—and with the cruel lines added to a Negro engine wiper’s mournful song by a Tin Pan Alley hack. “The Casey Jones song has haunted my whole life since the beginning of the century,” she once said. Memphis railroaders were known to fight with strangers who sang the slanderous lines. For a while, the ballad was banned in Jackson, Tenn., where Janie Jones lived out the long, lean years. With the help of a ghost writer, she tried to clear herself in a new version of the song: “My Casey, Husband Casey, who meant the world to me.”

Thank, you Kimberly. The history of Casey Jones is woven into the cultural fabric of America. Postings like this, hopefully, will keep it that way.

LikeLiked by 2 people

wow he was really a very good guy

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the history and quote from Janie! What a great find! And the wonderful picture. I wonder why the media had so much animosity toward her? They sound disrespectful toward her!

LikeLike

Casey Jones was certainly a hero and Janie was a loving wife that kept fighting for her husband’s reputation. The “musicians” singing disparaging lyrics would have been the first ones to jump from the train!

LikeLiked by 2 people

i admire him but i sure would’ve jumped

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, Ruby. The crash was inevitable. Why die for the inevitable?

I have to remind myself it was a passenger train and the only fatal injury was to Casey Jones. There was one other injury to the Baggageman by the name of Miller. He sustained broken ribs when the baggage car derailed and climbed an embankment.

The facts are, due to no fault of Jones, the train left very late. I’ve read two reported times of how late it was: 75 minutes and 95 minutes. Casey was “highballing” (a railroad term for running at excessive speeds) the entire trip. A 100 miles run between two water stops early in the trip and the time he made up meant that he was (estimated) to have been traveling at 80 mph. That likely was a factor in not being able to stop the train before it collided with the freight cars. If traveling at normal speed, he may have been able to stop before colliding.

Also, it was a “Perfect Storm.” Casey “highballing” to arrive on time and two exceptionally long freight train that were stopped at the station causing a string of cars to extend over the main line used by the passenger train.

Steam engines of the early 1900s had horsepower ranging from 100 to 700. That is a lot of horses! But in railroading engine power is measured in tractive effort, the measure of its pulling and pushing power. Tractive efforts inversely acts with speed. At a high speed a train requires less horsepower to maintain the fixed speed. But, that means the faster the speed of a train the more track is required for it to come to a complete halt; a train in motion has kinetic energy that must be reduced for it to stop.

The kinetic energy of a train is reduced by the brakes being applied to the wheels, causing friction between the wheels and the rails. If the speed of Casey’s train was 40 mph when it hit the freight cars, he was “highballing” it when he applied the brakes. Casey just did’t have enough rail distance at the speed he was traveling to stop the inertia of the train. BUT, he did save the lives of the passengers by doing what he did . . . . . sacrificing his own life.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Nicola, I think some people on Reddit saw your comment before I did. I posted a link to this story in a couple of sub-reddits and saw a few people allude to some of the history in your comment. I was surprised that several people knew details about a relatively obscure piece of history— now I see why! That’s really cool! 😎

LikeLiked by 1 person

Molte grazie!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe that “History” is an interesting subject when personal anecdotal facts are told. That makes “History” personal and not just a broad series of events to memorize. I had an outstanding U.S. History professor who taught on that basis. Because of him, I know of Crispus Attucks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like a very interesting story! Maybe you’ll write it for us one day?

LikeLike

Me too, Ruby! I’m no hero but I admire heroes

LikeLike

100%! Casey was the man in the arena, wasn’t he? Definitely not the critics.

LikeLike

A critic opines as though they know everything about something and finds fault with everything except themselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So true. It’s why we have to admire the man in the arena!

LikeLike