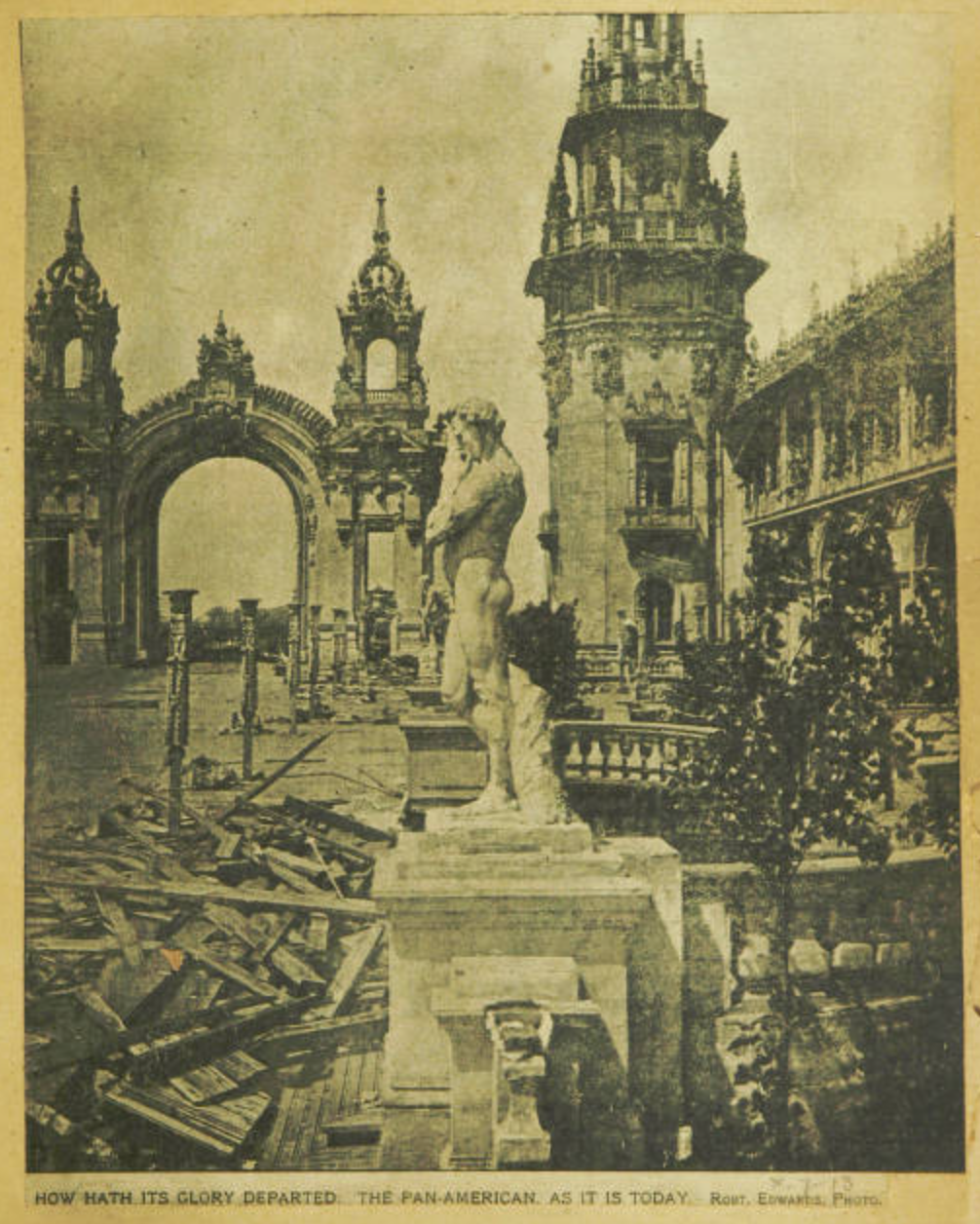

From May to November 1901, Buffalo hosted the Pan-American Exposition. Perhaps the highlight of the Exposition were the millions of electric lights, powered by hydroelectricity from Niagara Falls. Most people in the world had never seen an electric light. They were awe-struck by Buffalo’s Pan-Am.

At the center of the fair was the massive Electric Tower, and poised at the top was the Goddess of Light statue, illuminated by over 40,000 lights.

I found a scrapbook with an article from the Buffalo Courier written in 1902, during the demolition of the fair grounds. It’s a tongue-in-cheek little piece about the inglorious end of the Goddess of Light. I can’t improve on it, so I’ll give it to you intact!

Suicide of a Goddess

The glorious, gilded, shimmering, dazzling, Bacchanalian creature which tiptoed on the extreme apex of the famous electric tower all last year at the Pan-American Exposition, and was the central feature of a thousand stories of the splendor and fascinations of that fete, will not go to Cleveland to be humiliated.

There was a limit to that damsel’s pride. If she was good enough to be hoisted to the highest pinnacle of distinction at the greatest of all American expositions, she was too distinguished, certainly, to become the object of the raillery of a peanutty crowd of revellers in an obscure park in an obscure city.

She! She, who had queened it over millions and tens of millions, whose sovereignty had been acknowledged by the fairest women and greatest men of all climes, whose grace and contour and feminine charms had been lauded by poets and preserved by a hundred thousand amateur photographers-set up to be scoffed at, perhaps, by the ignorant and unwise and the hoodlums—horrible. She was above all such dangers at the tip of the Electric Tower.

If there was anyone to speak a word of derision she was above hearing it—395 feet, or was it 401 feet?—above it.

Hundreds of thousands of enthusiastic people had shouted their acclamations as the bright Mayday sun first cast its amorous rays upon her and caused her to glow with a refulgence that was as becoming as the blush of pink on a maiden’s cheek. She had heard the roar of applause and had intuitively known that it was her own curtain call; and she had heard it again when the full summer moon had shed upon her shapely form the mellow radiance of its illumination.

These were remembrances which she was determined should never be blotted out.

She remained at her post throughout the winter, proudly defying the elements and holding her head as haughtily as the premier duchess might at a coronation. Sometimes she wondered what was to become of her, for there were unmistakable evidences of demolition going on at her feet.

One stormy day her twelve-inch ear intercepted a Marconi message:

“From Cleveland. Harris & Company, Exposition Wreckers, Buffalo.

“What will you take for the Goddess of Light. Wanted here for a popcorn pavilion.”

A shiver ran up her steel spine. For a moment, when no one was looking, she buried her head in her arms, and wept great tears which drummed on her hollow legs and fell with a painful splash in the basin, four hundred feet below. But she soon recovered her equanimity—the Exposition Company took care of her equilibrium—and it was then that she resolved that come what might she would never be so humiliated. Cleveland—of all places! A popcorn joint—of all thrones. It were far better to be enthroned in the memory of those who had bowed before her as the Goddess of Light, than to descend from such a lofty estate and accept a mean sovereignty over such a poor kingdom.

Fully determined, she awaited the oncoming of the wreckers.

Weeks passed and summer came again. And with the cold, showery June came a gang of men who bound her with ropes preparatory to her dignified descent to earth and to preserve her for the bondage to which she had been condemned, for so she considered the “honor” which was sought to be conferred upon her.

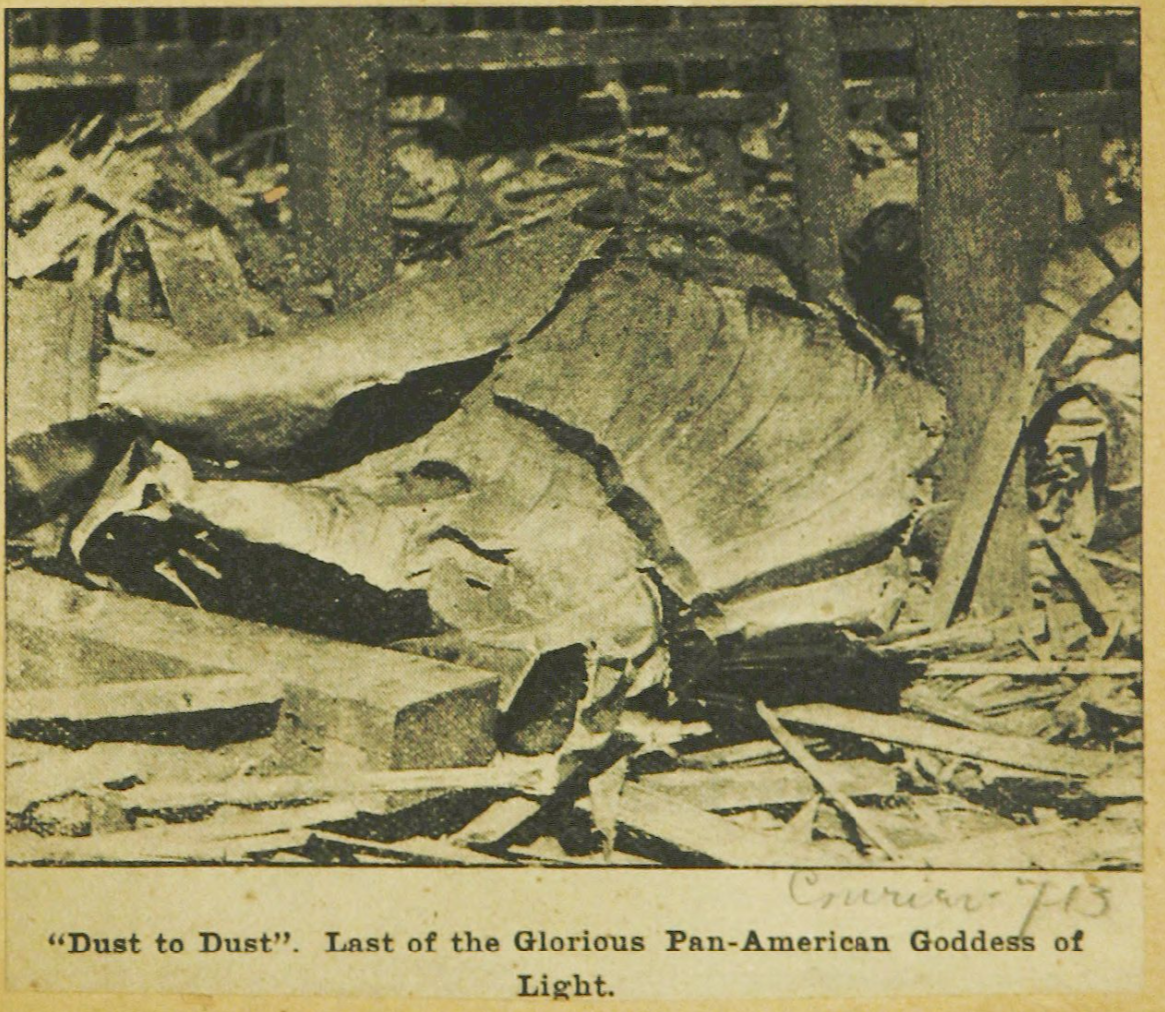

Bolts were loosened and when the opportunity offered the proud creature sprang from her pedestal, shrieking, “Welcome, sweet death,” and was crushed into a shapeless mass at the foot of the tower.

There she was photographed for a last time by the Sunday Courier photographer—the pitiful remains of the highest royal dignitary who ever held sway over a dominion of millions of admiring people.

“Safe in a ditch she bides

With twenty trenched gashes on her head

The least a death to nature.”

It was a tragic finale to the transcendant comedy over which the Goddess of Light had reigned as the loveliest queen of all expositions. Raised on her lofty pedestal, she was the joyous and gracious antithesis of that other female who “sat on a monument, smiling at Grief.” Her thirty feet of stature are compressed into a few ragged and crushed sections of galvanized iron. There is still a trace of the gold leaf which reflected the brilliance of the noonday sun, the radiance of the midsummer moon and the translucent glow of the Electric Tower beneath her feet, but she is self-wrecked so completely that there is no hope of restoring her majesty to her original form and her remains probably have gone ere this to the junkshop.

Bye-bye, Goddess, and ta-ta. You did your part well. Your discretion and your proud hauteur could not have been improved upon. Peace to your pieces.

I’ll be joining a virtual event at the Burchfield Penney museum’s book club on Thursday, February 5 to talk about my book Cold Heart and the mysterious murder of Ed Burdick in Buffalo in 1903! The event is free and open to the public! Visit the Burchfield Penney Art Center website to register. I hope to see you there!

The pejorative terms used by the Buffalo journalist in reference to Cleveland ignores the fact that the Pan-American Exhibition was the attraction not the city of Buffalo itself. The cities were comparable in 1901, with Cleveland having a marginally larger population.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s true but… as a native Ohioan who grew up near Cleveland, I can sympathize with the Goddess of Light’s predicament. Working at a peanut stand is a less-than-delightful prospect!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lol!

LikeLike

My career caused me to live in North Canton, OH, for two years, about 50 miles from Cleveland. For many reasons I made trips to Cleveland; as a matter of fact we made regular trips there because we discovered a pizza joint close to the “pies” we were accustomed to in the northeast.

My family enjoyed the short time in Ohio. We lived about 6 miles from the Football Hall Of Fame and, at the time, it was the home of The Hoover Company. As a matter of fact, the first vacuum cleaner was invented in North Canton, OH, in 1906 by a department store janitor and part-time inventor James Murray Spangler. Oh, I shouldn’t forget that 15 miles up the Interstate was Akron, OH, the one time home of the American tire industry.

LikeLike

It could have been worse. What if it was sent to Toledo, Ohio?

LikeLike