I wrote this post ten years ago, on March 1, 2015. In general, I don’t like to repost but, with the wildfires raging in LA, this story came into my mind more than once.

Let’s investigate, shall we?

Chicago’s Iroquois Theater opened in 1903 on West Randolph Street. No expense was spared on the massive, L-shaped structure. From the soaring ceilings to the mahogany trim to the gilded accents, the theater was magnificent. It was a work of art. It had three levels and could accommodate 1,700 people.

Owner Will Davis expected the theater to be complete by the summer of 1903, but the opening was delayed by labor disputes.

In October, fire-related safety concerns threatened another delay. An inspection noted a number of deficiencies, including an absence of proper air flow. Iron gates, designed to keep people from sneaking in to the shows without buying a ticket, blocked many of the exits. The mahogany trim was beautiful but it increased the fire hazards in the theater.

If a fire did break out, the Iroquois was ill-equipped to handle it. There were no fire extinguishers, sprinklers, or water connections. The fire-fighting equipment was limited to a half a dozen canisters of a bicarbonate soda compound used to snuff out kitchen fires.

Davis was irate at the threat of another delay and determined his theater would open in November, come what would. Corrupt city officials accepted bribes from Davis and, despite the howls of the Fire Department, the Iroquois Theater’s grand opening took place in November 1903.

As attractive as the building itself was, certainly one of the big draws to the public was the incredible claim that the Iroquois was fire-proof. America was paranoid about fire in 1903. Fires in public buildings were still a common occurrence. The city of Chicago suffered tremendously during the Great Fire 30 years earlier. That blaze had cost 300 lives and millions of dollars in damages.

Like the unsinkable Titanic, the fire-proof Iroquois was destined to become a grim lesson that we shouldn’t label anything as 100% immune to tragedy. Why tempt fate?

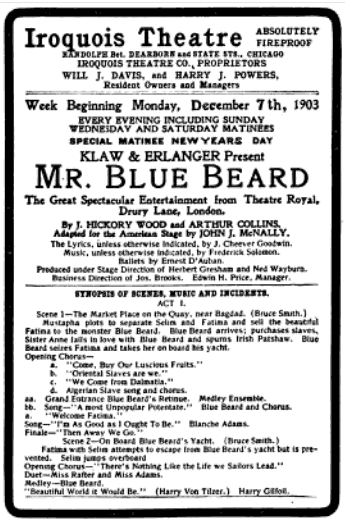

For five weeks, the Iroquois Theater flourished. The children’s musical Mr. Blue Beard was a daily attraction and the investments Will Davis had made in marketing the show were paying off. Families crowded into each performance.

December 30, 1903 was another sold-out performance. At least 2,100 people were present, well over the building’s maximum capacity of 1,700.

Eddie Foy was one of the actors in Mr. Blue Beard. He had brought his son Brian to see the performance, but the show was sold out. The child, unperturbed, stood in the wings watching the show.

Years later, Foy wrote of that afternoon performance. “It struck me as I looked out over the crowd during the first act that I had never before seen so many women and children in the audience. Even the gallery was full of mothers and children.”

The show continued smoothly until 3:15 p.m. It was time for a musical number. The theater was darkened and the only light emanated from a spotlight that was trained on the stage. In the glare, eight couples ascended the stage to sing “Let Us Swear It by the Pale Moonlight.”

No one is sure exactly how the fire started but the general consensus is that the spotlight probably short-circuited.

A ribbon of flame ignited on the oil-painted backdrops suspended over the stage.

The stage manager saw it immediately and seized a canister of the fire-fighting compound. He sprayed the flames with it but the watery solution merely dripped off the hanging backdrop onto the stage. He watched in horror as the flames leapt from one backdrop to the next.

There was no way to hide what was happening. The auditorium was dark except for the stage, and audience members spotted the flames at once. Shrieks filled the auditorium and panic set it at once as smoke filled the theater. In the darkness the people began to rush forward blindly, seeking an exit.

Most of the cast and crew did not leave immediately. Some of the crew attempted to lower an asbestos curtain to smother the flames but it jammed half-way down. It was too thin to be effective anyway. In a moment, it too ignited.

The theater had no telephone. While that wasn’t unusual at the time, a public building the size of the Iroquois ought to have had a fire-alarm box. It didn’t. As soon as the fire started, one of the stagehands was told to run to the nearest fire station for help.

The cast, crew, and theater staff was well aware the spreading fire wasn’t the only grave danger. Fires often resulted in a stampede, where people were trampled to death. Some ushers ran into the aisles, attempting to quell the panic. The stage manager ordered the orchestra to keep playing, hoping it would calm people. Eddie Foy pushed his son into the arms of a crew member and ran onto the burning stage, determined to prevent a catastrophe. “Be calm!” he shouted over and over. “Leave in an orderly way!”

The staff at the Iroquois was new and some didn’t know where the exits were. Some exits were hidden by drapery and some were locked. The architects had also designed a number of doors that turned out to be ornamental. The exits that were open could not accommodate the surge of people, desperately attempting to escape.

Flames soon engulfed the orchestra seats, the gallery, and the dress circle levels.

In the balconies, chances of escape were slim. Some theater-goers jumped onto the main floor. Others found a fire escape at the back of the building, people raced down several stories of icy narrow steps, to escape into the alley. This route was soon cut off by flames. The terrified screaming crowd forced those at the front to jump to their deaths.

The cast and crew pushed into the frigid night from the exit behind the burning stage. The inadequate ventilation caused the outdoor air to blow the flames out into the crowd. The burning sets suspended overhead gave way and crashed onto the stage, forcing Eddie Foy to flee the theater.

The carnage from the fire was dreadful. More than 600 people were dead and hundreds more were injured. Hundreds of people were found at the base of the stairways, having been trampled or asphyxiated. Many people who reached the fire escapes fell to their deaths. Many bodies were by one of the ornamental doors.

It’s nearly forgotten today, but the Iroquois Theater fire remains the deadliest single-building fire on record in the US.

Immediately after the fire, Chicago mayor Carter Harrison closed all theaters for six weeks and banned public celebration on New Year’s Eve. That wasn’t enough for outraged Chicago. The people demanded someone be held accountable for this disaster. A disaster which might have been easily prevented, or at least minimized. Will Davis, theater manager Harry Powers, Mayor Harrison, and numerous city officials were charged with crimes related to the Iroquois fire.

Thanks to some slippery defense attorneys, the charges were dismissed and no compensation was given to the victims and their families. In fact, only one person was ever convicted of a crime related to the fire: a bar owner, whose establishment served as a temporary morgue, was convicted of robbing the bodies of the dead.

Eddie Foy, the actor who risked his life to calm the crowd, was credited with saving many lives after the fire broke out. When he burst into the alley behind the burning theater, he found his own son, Brian, unharmed and waiting to greet him.

If you liked this post, please subscribe to Old Spirituals, like and share the post on your social media, and leave a comment! It really helps other people find the site. And if you’re so inclined, check out my books on Amazon or Buy Me a Coffee!

Fire is a unique kind of disaster. All the terrible fire stories have certain commonalities.

-Easily preventable

-People in charge were warned in advance about fire and refused to take precautionary measures

-Greed/corruption played a key role

-The people responsible for all the misery walked away scot-free

Have you heard of the Triangle fire in New York City? It happened around this time but it was a factory that violated all the safety codes. A lot of working women lost their lives in that fire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a really good point, Ruby! Fires usually have an element of human recklessness to them. I actually wrote about the triangle fire back in 2013. https://oldspirituals.com/2013/12/01/triangle-fire/

LikeLiked by 1 person